The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism Before the Revolution

February 2025 Book Club Discussion Thread

In “The Making of Holy Russia”, Fr. John Strickland provides a fascinating historical account of late imperial Russia from 1881 to 1917, examining how Orthodox Church leaders sought to revitalize Russian society with Orthodox Christianity as the foundation of Russian identity.

The book centers on what Strickland calls “Orthodox patriotism," a movement that emerged following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 and continued until the Bolshevik Revolution. This was a period of tremendous social and political upheaval in Russia, with revolutionary movements gaining strength while the Orthodox Church faced the threat of secularization and Western influence. During these conditions, the Russian people preserved Holy Orthodoxy in their hearts in a manner that embedded the true faith into the Russian spirit and transmitted through perseverance of the Slavic race (p.21).

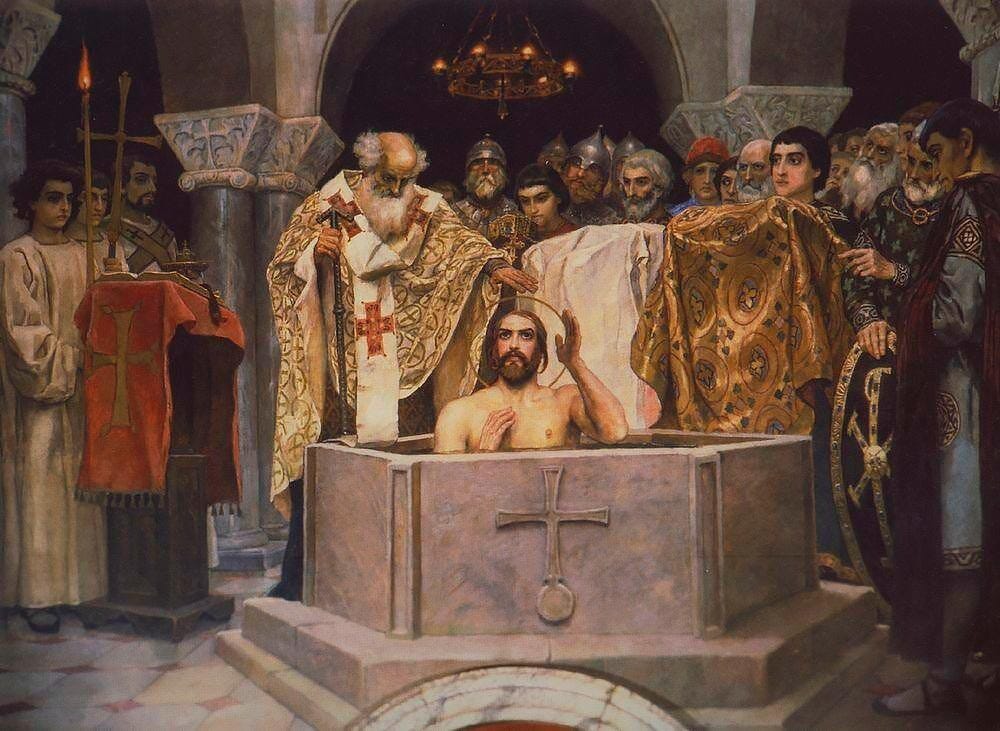

Fr. Strickland begins his account with the 900 year commemoration of the baptism of Rus in 1888, using the milestone celebration as a glimse into how Church leaders were actively constructing and promoting a vision of Holy Russia. What becomes clear through his careful analysis is that this concept was being piously cultivated in response to modern challenges.

While Byzantium was thought of as the New Rome, Holy Rus became known as the "Third Rome" and "New Israel" which deeply shaped the Russian identity. Metropolitan Ilarion of Kiev (1051-1055) even boldly declared the Russian people to be "direct successors to Israel," establishing a powerful narrative of divine election and spiritual inheritance. Later, following the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the monk Philotheus advanced the notion that Moscow had become the Third Rome, inheriting the mantle of Orthodox Christianity after the fall of Rome and then Byzantium.

As Fr. Strickland explains, the concept of Third Rome positioned Russia as "the eschatological fulfillment of Christian history”, a nation with "a calling, a kind of ministry in history to preserve Orthodox Christianity until the end of time." While Fr. Strickland notes this doctrine wasn't widely embraced during the Muscovite period, it reemerged powerfully during the 19th century Orthodox patriotic revival. The linking of Russia directly to biblical Israel positioned it as Christianity's final earthly defender, providing powerful Orthodox foundations for Russian identity, despite the risk of elevating national particularism above Orthodoxy.

Unlike the Western post-Reformation model of church-state separation, the Orthodox tradition envisioned a more integrated relationship where the state existed within the church rather than as a separate entity. Throughout the book is the constant reminder that separation between Church and state is completely contradictory to western models of governance. A prominent example can be seen in the continual efforts of the Russian Empire to maintain statecraft in the harmonious relationship between the minds of Church leaders and state known as “symphonia”, which characterized Byzantine civilization. This model of apostle-like statecraft, exemplified by figures like Vladimir the Great, sought to sanctify governance itself through a synergism of spiritual, cultural and political eschatology of the Kingdom of God on earth (p.116).

The Orthodox patriots of late imperial Russia were attempting to recover symphonia during a period when it had been significantly weakened by Western influenced reforms under Peter the Great and Catherine the Great. Their vision stood in opposition to both the state domination of the Church established by Peter's reforms and the emerging secular nationalism of the modern era, which represented an attempt to return to an integrated spiritual-political model.

Fr. Strickland draws special attention to the paradoxical tension the Orthodox patriots navigated in a delicate balance between modern nationalism and commitment to the universal truth of Orthodoxy. They emphasized a strong Russian national identity as a vehicle for spiritual renewal while avoiding nationalism's most destructive tendencies.

To further highlight pre-revolution Russia’s rich Orthodox culture, Fr. Strickland notes how music and art played a unique role in integrating national identity with the Church. Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was commissioned for the consecration of Christ the Savior Cathedral while painters like Mikhail Nesterov depicted an idealized Orthodox Russia. Perhaps most striking is Fr. Strickland’s account of how Tsar St. Nicholas II contributed to the construction of nearly 6,000 churches in 1908 alone, literally transforming the imperial capital to a grandiose medieval style cityscape to reflect Russia's Orthodox heritage.

Fr. Strickland remains neutral in his analysis by avoiding simplistic judgments about the nature of Orthodox patriotism. Instead, he presents the movement in all its complexity – as a sincere spiritual endeavor that ultimately became entangled with political ideologies and the fate of the Russian autocracy.

For those interested in Russian Orthodox history or broader questions about Orthodoxy's relationship to politics and culture, The Making of Holy Russia serves as an incredibly valuable yet relatively challenging read. It is a window into a pivotal and complex period in modern Church history that continues to influence Russian cultural and religious identity today

Whether you are still making your way through the book or have completed the reading, please share your thoughts and insights in the comments. I read every response and would love to hear your feedback.

Not a member yet? Join The Reversion Book Club today and become part of a growing community of like-minded Orthodox Christians developing life-long skills for knowledge acquisition.

Hello! I am enjoying your blog very much! Can you please give the title and artist for all the wonderful scenes in this article? I would appreciate it. Thank you