The Secularization of Christmas Pt. 1: Santa the Shaman

How the beloved Saint Nicholas became depicted a shamanistic goat-riding magician known as "Father Christmas"

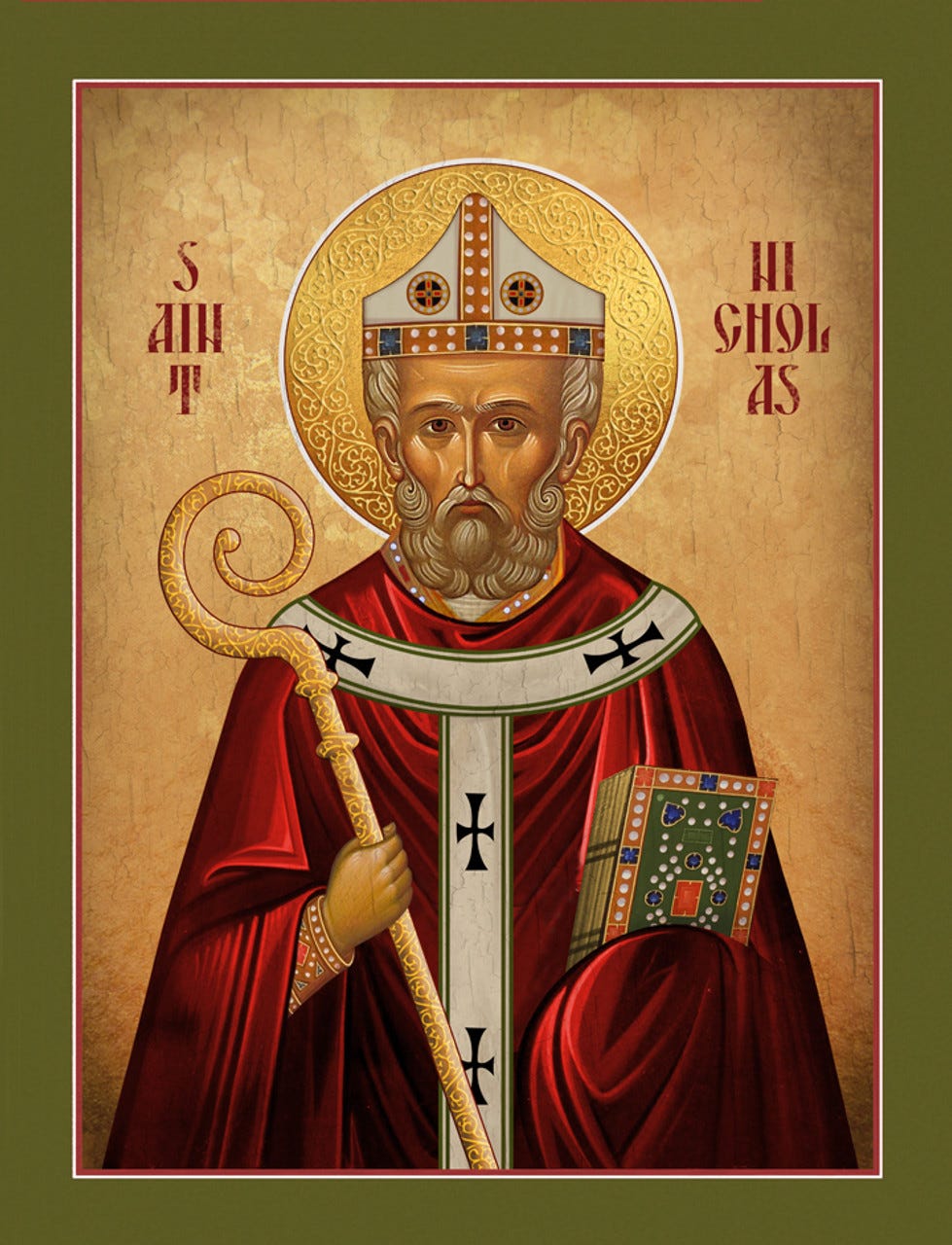

On the feast day of St. Nicholas, we are reminded through the various memes that Santa Claus is in fact real and if you disagree, you must be a Reddit user and Funko Pop collector. Although I am continually prompted to reflect upon both the subtle and more obvious shifts within seemingly innocent traditions—changes that, whether intentional or not, carry a subversive anti-Christian element. The transformation of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, the 4th-century bishop of Myra and Lycia, into the secular figure now recognized as Santa Claus, is one of those more subtle shifts that we are mostly aware of but also can’t quite explain.

How did the beloved St. Nicholas become Santa Claus—a fat cookie eating chimney climber who navigates through the sky on magic flying reindeer?

St. Nicholas is one of the greatest saints of the Church, famous for his charity and wonderworking miracles. He was imprisoned for his faith under the great persecutions of Diocletian. "With the accession of Constantine, St. Nicholas was very zealous for the destruction of idolatrous temples and for the driving out the demons that inhabited them." He was a key figure at the 1st Ecumenical Council of Nicea where he famously punched the heretic Arius in the face for blaspheming Christ. His relics have worked countless miracles to this day.

According to the Synaxarion, on three occasions, St Nicholas secretly left gold enough for the marriage portions of three maidens whom their debt-ridden father intended to give up to prostitution. When the man eventually discovered his good deed, Nicholas made him promise, as he valued his salvation, to tell no one of it.

“The enemies of the Church, however, could not support the popular fame of St. Nicholas among children and invented another figure to divert their attention.”1

Various European cultures embraced the feast day of St. Nicholas on December 6th, intertwining acts of charity and gift-giving with their unique traditions. This cultural amalgamation laid the groundwork for the evolution of the gift-giving saint associated with the Christmas season which “instead represented a kind of philanthropy without a religious foundation, without the highest cause. This was the way the religious legend of St. Nicholas became a profane, or secular, legend in France.”2

The Dutch diaspora played a significant role in shaping the character of Santa Claus. Dutch settlers transported with them the Sinterklaas tradition, a figure based on St. Nicholas, celebrated on December 6th. Rooted in the spirit of gift-giving, this tradition included a character known as "Kris Kringle" or "Christkind." As these customs intermingled with Christmas celebrations in English-speaking colonies, a new narrative began to unfold.

The Santa Claus moniker itself, transitioning from the Dutch "Sinterklaas" to "Santa Claus," represents a linguistic transmutation, symbolic of the secularization of a feast day celebrating the wonderworking saint. Dutch Pilgrims in the New World brought their Sinterklaas tradition with them to America. Sinterklaas is a Dutch figure based on St. Nicholas, and the Dutch celebrated his feast day on December 6th.

Protestants, who hated the cult of the saints, substituted the legend of St. Nicholas or St. Claus with the legend of a Nordic magician. Then they mixed many characteristics of the magician – the sleigh, reindeer, etc. – together with the life of St. Nicholas to deviate the admiration of the children from a religious figure to a fantasy.