Read Time: 30 minutes

Authors Note: This is part two of an ongoing series. Part one can be read here.

Contents:

The Invisible College of the New World

Early Millenarian Cults of Christian Zionism

False Messiah in the Year of Apocalypse

The Judeo-Masonic Republic

The Dispensationalism Delusion

Scofield’s Talmudic Scam Goes Viral

The Jewish Messianic Age of Antichrist

Kabbalistic Chaos and The Ark of Salvation

“The occupation of any kind of occultism (including Kabbalah) introduces a person into communication with fallen spirits. Infected by the disease of vanity and, having no spiritual vision, to see a yawning abyss in front, such a person turns out to be enslaved by demons. All the classes of magic and occultism end in spiritual death.”1 —Heiromonk Job (Humerov)

The Invisible College of the New World

With a popular new interpretation of Kabbalah by Isaac Luria, a spiritual blueprint for the New World was born in the magic and occult science of the English sorcerer John Dee. In addition to being the advisor to Elizabeth I, Dee was known as the foremost genius of the sixteenth century, amassing a personal library of over four thousand books, many of which he salvaged from Roman Catholic monasteries and churches that were sacked during the Reformation.

Dee spent his days in his library, immersed in Kabbalistic mysteries and a multitude of obscure esoteric studies such as Enochian magic. One of Dee’s bizarre occult practices involved gazing into crystals to communicate with evil spirits which he believed to be angels. Hundreds of Dee’s conversations with spirits were recorded in a supposed pre-Hebraic language by his companion Edward Kelley, an alleged necromancer who helped Dee develop the Enochian system of magic.

In his book John Dee and the Empire of Angels, Jason Louv argues that “with Luther’s proposed break with Rome, and Henry VIII actualizing it in England, Dee created the plan for global Protestant victory over the Church.” He continues:

Such a global Protestant hegemony would pave the way toward the Second Coming, and central to actualizing this plan was Dee’s angelic system of [Enochian] magic. For Dee, and many to follow him, it was thought necessary to help this occur through enlightened human activity—the Great Work. Indeed the second half of Dee’s life was consumed by following the dictates of impatient angels intent on using human agents to advance history toward the Apocalypse.2

After a life of alienation and exile, Dee spent his last days leading an alchemical reform movement in Prague, which had undergone a renaissance of Kabbalistic enlightenment during a golden age of Jewry. By 1614, Dee’s work was crystallized in the Rosicrucian manifestos written by Johann Valentin Andreae, a Protestant theologian in Württemberg.

Through the mass dissemination of Andreae’s Rosicrucian literature, notions of an Invisible College of elite magicians quickly became embedded into the consciousness of intellectuals throughout Europe. Andreae had also notably published a pamphlet called Description of the Republic of Christianopolis to dismiss the Rosicrucian order as a myth, despite he himself having written the manifestos. In it, he further described a Masonic Christian utopia ruled by science, Kabbalah, sacred geometry, and archangels such as Uriel,3 whom Dee claimed to derive his Enochian magic from.

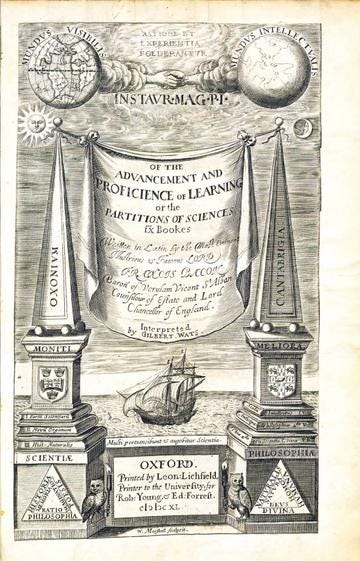

Yates argued that another key influence parallel to Dee’s esoteric plan to reform the New World into a utopian Protestant hegemony was Francis Bacon. Posthumously published eight years after Andreae’s Description of the Republic of Christianopolis, Bacon’s utopian novel New Atlantis envisioned a clandestine Christian institution called “Salomon’s House,” an invisible college comprised of illuminated Rosicrucians who ruled the land with advanced scientific knowledge.

The twentieth century occultist Manly P. Hall had no doubts that America embodied Bacon’s utopian ideal of a New Atlantis and the Rosicrucian plan to liberate Europe, guided by the French and and American revolutions.4 Bacon himself even alluded to the establishment of Salomon’s House as a blueprint for America in a speech to Parliament.5

Protestant secret societies are not only an eighteenth century phenomena; they emerged through the Rosicrucian Order alongside the Reformation, intersecting as a Hermetic counter-balance to the Roman Catholic Jesuits. In the decades proceeding Bacon’s death, the Rosicrucians actualized the “Invisible College,” modeled after the Salomon’s House, whose giants of humanism included René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Johannes Kepler, and Isaac Newton.

The Invisible College later became the Royal Society in 1647, based on Bacon’s scientific method, which the Masonic founding fathers drew from to construct the empirical principles of American values.6

Early Millenarian Cults of Christian Zionism

Christian support for a Jewish messianic kingdom on earth is an entirely Protestant notion that arose not as a modern phenomenon but during Puritan England’s Hebraic revival in the seventeenth century. In fact, Puritan judaizing was so common during this time that practices such as Sabbatarianism, later became enshrined in the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith. Henry Hallam recalls, “During no period of equal length since the Revival of Letters has the knowledge of the Hebrew language apparently been so much diffused throughout the literary world as this.”7

In a surge of end-times anxiety, many Puritans drew from literal readings of the book of Revelation to associate the upcoming year of 1666 with the number of the beast, believing it to be the year of the apocalypse and second coming. As a result, it was common for Puritans to correspond with Menasseh ben Israel, a renowned Kabbalist rabbi from Amsterdam, to understand the Jewish prophecies concerning the messiah.

The Jewish community was thriving in seventeenth century Amsterdam and even became known as “the Dutch Jerusalem,” attracting hordes of conversos who found refuge in maintaining their Jewish identity after fleeing persecution from the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal.

In England, Thomas Brightman inspired a Millenarian admissionist movement with his hyper-literal commentaries on Biblical prophecies and one of the earliest known proto-Zionist works entitled Shall They Return to Jerusalem Again?. The movement helped bolster support for Jewish immigration by many prominent English Puritan ministers such as John Cotton and Thomas Barlow, the teacher of the Calvinist titan John Owen. Most notable among the English millenarians was Oliver Cromwell, who developed correspondence with Menasseh in a plot to execute King Charles in 1649.8

Cromwell later terminated Parliament and the Commonwealth in 1653 and appointed himself as Lord Protector in what English utopian novelist Samuel Butler regarded as a Rosicrucian circle.9 Menasseh was strongly convinced that a necessary condition for the Messianic age required a mass resettlement of Jews across the world, so he sought to collaborate with English millenarians interested in Kabbalah in an effort to readmit the Jews to England after a 400-year expulsion by Edward I.

To fulfill this Kabbalistic plan, Menasseh collaborated with Calvinist minister John Dury, Moravian bishop John Amos Comenius, and Samuel Hartlib the “Great Intelligencer of Europe,” to form a Baconian style Invisible College known as the Hartlib Circle. This extensive network was revealed in the recent discovery of an archive containing over twenty-five thousand papers Hartlib amassed in an effort to "record all human knowledge and to make it universally available for the education of all mankind.”10

Hartlib’s network reached from New England to Western Europe and included Protestant poet John Milton, author of Paradise Lost, and John Winthrop, a Puritan Kabbalist leader in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and follower of John Dee.11

By 1656, the fervent anticipation for a coming messiah among Puritans was so prevalent, one English Quaker leader named James Nayler, “declared that he was Jesus Christ and rode into Bristol, re-enacting Jesus' entrance into Jerusalem.” Popkin recalls how Nayler “also supposed to have raised a Quakeress from the grave while his followers chanted "Hosanna in the highest," and called him the king of the Jews.”12 Despite Cromwell’s defense of Nayler’s extreme delusion, he was arrested and convicted for blasphemy. After being jailed, his followers fled to Amsterdam, the Levant and the American colonies.13

If Theodore Herzl is known as the father of modern Zionism, it can be said the father of proto-Zionism is the millenarian Kabbalist Isaac La Peyrére. As a Hugenot and alleged Marrano, La Peyrére was a devout Messianist who believed the Jews needed to join with Christians and the king of France in preparation for an imminent coming of the messiah. On his way back from a 1654 meeting in Belgium with La Peyrére and Queen Christina of Sweden, Menasseh experienced a seminal moment that would reshape the world. David Livingstone recalls:

After reading La Peyrère’s Du Rappel des Juifs (The Return of the Jews), Menasseh rushed back to Amsterdam where he excitedly told a gathering of Millenarians at the home of John Dury’s schoolmate and friend, Peter Serrarius, that the coming of the Jewish Messiah was imminent. Menasseh had departed for England to present a petition to Cromwell. Cromwell summoned the most notable statesmen, lawyers, and theologians of the day to the Whitehall Conference in December of 1655. The chief result was the declaration that “there was no law which forbade the Jews’ return to England.” Though nothing was done to regularize the position of the Jews, the door was opened to their gradual return.14

So, the Rosicrucians, Menasseh ben Israel, and the Hartlib Circle, working together with the Royal Society, mutated into a proactive acceleration of Christian Zionism at the same time that Luranic Kabbalah spread quickly into English Puritan communities. While apocalyptic speculation was rampant among Protestant Millenarian sects across Europe, Luria’s wildly popular Kabbalistic doctrines provided Jews with a new blueprint for a messianic kingdom. According to Robert Sepehr:

Part of this Kabbalistic method included ways of interpreting the supernatural relationship between events and time offered through letters and numbers. The magical emphasis given to the numerological value of dates contributed greatly to the widely held expectations and hope placed on the coming of a messiah at the time, particularly the 18th day, which is 6 + 6 + 6 of the 6th month of the year 1666.15

The viral dissemination of messianic pamphlets throughout Millenarian communities in Europe fanned the Kabbalistic flames of tikkun. Without the collaboration of Dury and Peter Serrarius, anticipation and acceptance of the coming pseudo-messiah Sabbatai Zevi among Puritans would not have been possible.

As dean of the dissident Millenarian theologians in Amsterdam and companion of Menasseh, Serrarius acted as a crier for the coming messianic age invoking Kabbalistic numerology (gematria) to set the stage for Zevi to reveal himself as the messiah in 1666.

False Messiah in the Year of Apocalypse

In 1666, England had just come out of a Great Plague with the Great Fire sweeping through London, priming the apocalyptic landscape for messianic fury. This period was described by John Evelyn in his study The History of Three Famous Imposters as “a year of wonders, of strange revelations in the world and particularly of blessing to the Jews, either conversion or restoration to their temporal Kingdom.”16 Millenarianist historian Richard Popkin describes the climate during this period:

When members of each religious community were drawn close together because of their common conviction that the end of days, the culmination of Protestant history, was about to take place…they developed theologies and theodicies that fused Judaism and Christianity. The various kinds of Jewish Christianity and Christian Judaism provided a powerful vital force for the messianic and millenarian movements of that time.17

During an unprecedented outpouring of messianic prophecy across Europe that Sabbatai Zevi of Smyrna declared to be the messiah in 1666. Despite nearly half the Jewish population becoming followers of Zevi, widespread Puritan millenarian activity alone made it possible for the Sabbatean revolution to gain Christian support throughout Europe. It’s expected of the Jews to be unable to discern the true Messiah from a false one, but Popkin argues “nothing is suggested that might show antecedent developments in Judaism that generated messianic hopes at the time.”18

Once again the printing press provided the technological means for the viral dissemination of judaizing heresies to immanentize the eschaton through human action. Popkin writes:

As is well known, there was a great deal of interest in the British Isles in Sabbatai Zevi's career. Almost as soon as he made public his messianic pretensions, pamphlets were appearing in England in English telling of marvelous, miraculous events that were occurring which indicated that the Restoration of Israel was at hand.19

Menasseh ben Israel’s influential teaching of dual messiahs, Zevi for the Jews and Jesus for gentiles, was spread through his millenarian correspondents including Dury, the famous apocalyptic preacher Jean de Labadie, and theologian Nathaniel Holmes, a student of Thomas Brightman.

Despite the simultaneous distribution of anti-Zevi pamphlets across England, many Protestants began to follow Zevi as the true messiah sent by God. Zevi’s messianic expectation came to a sudden halt in the same year when he converted to Islam under the threat of death, but his later followers would continue to remain loyal to the Sabbatean movement and the perverse antinomian practices that followed in its wake.

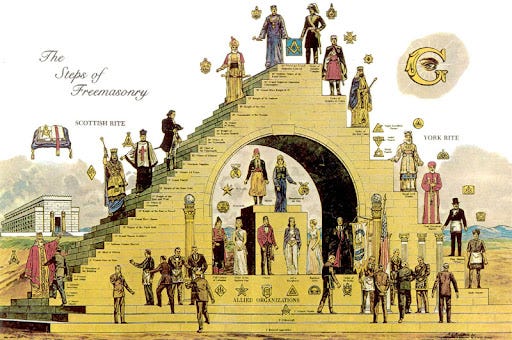

The Judeo-Masonic Republic

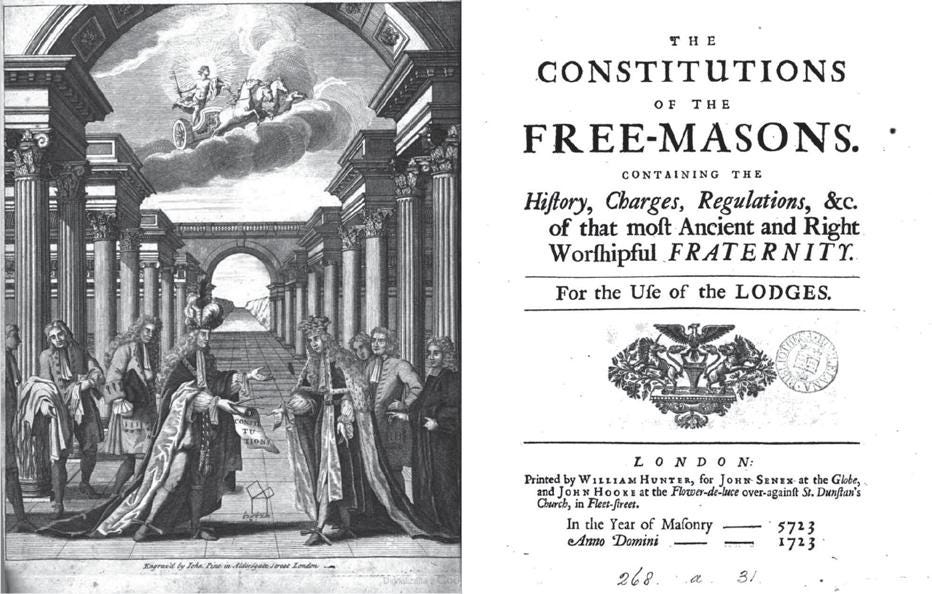

In exactly two centuries of fragmenting the Christian world, the Protestant Reformation of 1517 laid the groundwork for a new religious architecture of Freemasonry in 1717, as described in a 1917 issue of The Hamburger Fremdenblatt, commemorating Freemasonry's two hundredth anniversary and the Reformation's four hundredth anniversary. The article states, “It is a remarkable fact that the one rests on the other as on its foundation and that Freemasonry is inconceivable without Protestantism.”20

Liagre provides further insight as to how the relationship between Protestantism and Freemasonry developed in European society:

In Protestant countries, the Enlightenment was an alliance with the more liberal parts of Protestantism, and moreover, had no anti-religious impetus. The close ties between the Enlightenment and liberal Protestantism influenced Freemasonry in these regions, which led to a development of Freemasonry that is traceable in the different character of Masonry, for example in France and the Anglo-Saxon world.21

According to Fr. Seraphim Rose, Freemasonry is contextualized as a phase in history where man would search for a new religion beyond Christianity following the destruction of the Christian worldview by humanism and Protestantism.22 The Masonic lodges merely adopted the same Catholic humanism that Protestantism applied to the individual as an abstract papism—turning the new man into a subjective authority of infallible “truth” in place of an institutional body.23

As if echoing the Protestant Reformers, an explicit admission of this can be seen in the writings of the godfather of Freemasonry Albert Pike (1809–1891), who claimed:

No man or body of men can be infallible, and authorized to decide what other men shall believe, as to any tenet of faith. Except to those who first receive it, every religion and the truth of all inspired writings depend on human testimony and internal evidences, to be judged of by Reason and the wise analogies of Faith. Each man must necessarily have the right to judge of their truth for himself; because no one man can have any higher or better right to judge than another of equal information and intelligence.24

Yet humanism is just the exterior shell that embodies the Kabbalistic spirit of Freemasonry and the essence of the primordial man Adam Kadmon. E. Michael Jones comments that the religion of Freemasonry “is what Frances Yates would call Christian Kabbalah. It was the "scientific" reaction to the excesses of the Judaizing Englishmen known as Puritans. But the "science" in question derived, via people like Fludd, Bacon, and John Dee, from the Cabala, which was Jewish magic.”25

In his book The History of Magic, the influential Master Mason Éliphas Lévi reveals the eschatological role of Freemasonry in constructing the utopian infrastructure of Western civilization:

That great Kabalistical association known in Europe under the name of Masonry appeared suddenly in the world when revolt against the Church had just succeeded in dismembering Christian unity…

The allegorical end of Freemasonry to rebuild Solomon's Temple; the real end is the restoration of social unity by an alliance between reason and faith and by reverting to the principle of the hierarchy, based on science and virtue, the path of initiation and its ordeals serving as steps of ascent.26

Take note of how much emphasis is put on illumination, faith, wisdom, and virtue. These words have Kabbalistic meanings that are an inversion of the Orthodox Christian understanding, which we will examine later. It is through Lévi’s Kabbalistic lens, however, where we find the esoteric nature and purpose of Freemasonry; acting as a technological tool of social engineering to advance tikkun in an allegorical creation of a messianic Jewish utopia.

An 1861 French Jewish weekly journal titled La Vérité Israélite further supports Freemasonry’s perhaps not so allegorical aim:

The spirit of Freemasonry is the spirit of Judaism in its most fundamental beliefs; it is its ideas, its language, it is mostly its organization, the hopes which enlighten and support Israel. Its crowning will be that wonderful prayer house, of which Jerusalem will be the triumphal centre and symbol.

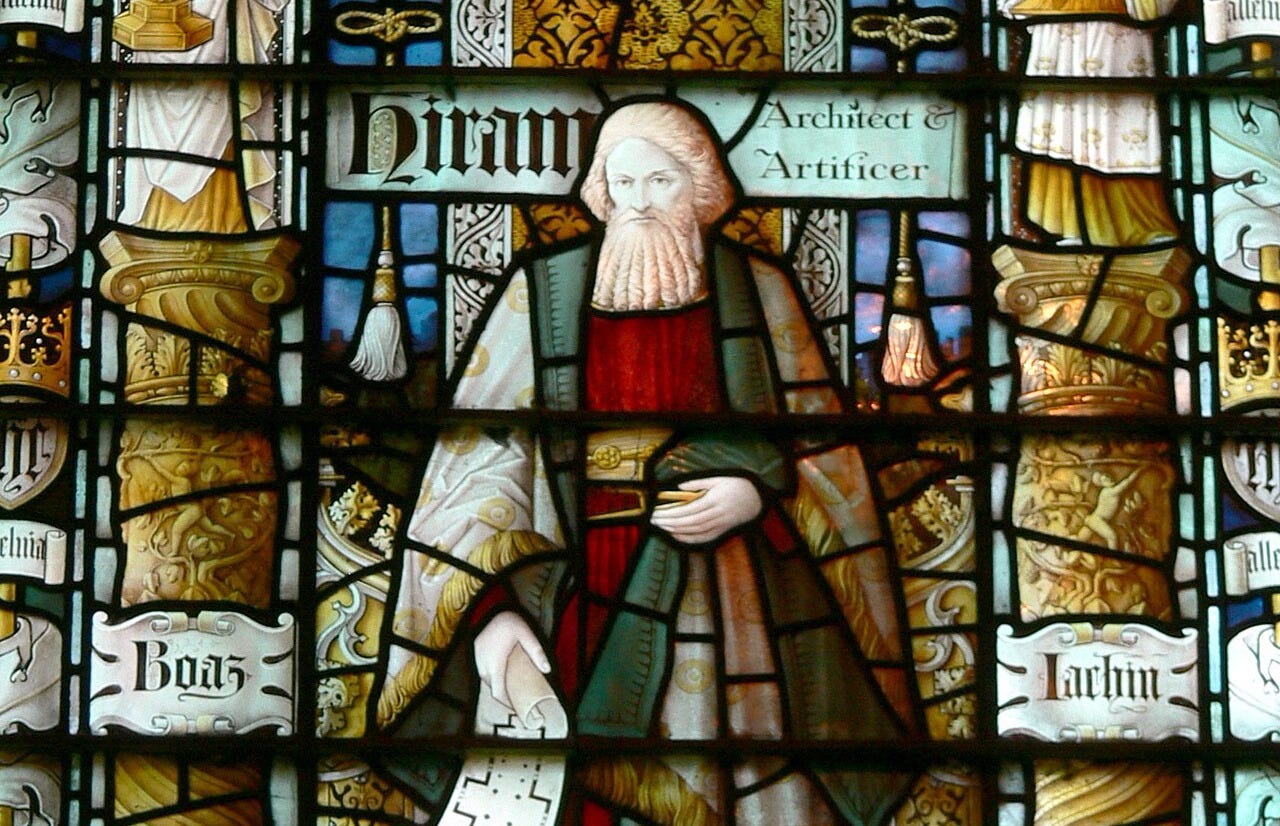

Continuing the work of Hiram Abiff, the mythical chief architect of Solomon’s temple, speculative or “mystical” Freemasonry is believed by Masons to be the modern evolution of the ancient craft guilds known as operative Freemasonry. Certain elements of Masonic lodges resemble the Temple of Solomon as degrees of ascent towards humanistic enlightenment, in a way symbolically marking this pivotal transition between the Reformation’s destruction of the old order and the Zionist utopia it helped to materialize. And to reach this final goal, Poncis writes:

“It was necessary to begin by undertaking the overthrow of monarchies representing the principles of authority and tradition, and to replace them, little by little, by the universal atheist masonic republic.”27

In order to both destroy the old Christian order and install what David Noble calls “The Religion of Technology” into the modern secular age, Masons employ the “useful arts” to reform the world by understanding, exploiting, and manipulating the natural world as a means of self-directed salvation.28 Noble goes on to illustrate:

Through Freemasonry, the apostles of the religion of technology passed their practical project of redemption on to the engineers, the new spiritual men, who subsequently forged their own millenarian myths, exclusive associations and rites of passage.29

It would be equally accurate to use Noble’s descriptor of Freemasonry as a technological project interchangeably with Protestantism in its ultimate dependence on the printing press, making it too a religion of technology.

Noble continues in describing the disproportionate role Freemasons played in the “Great Work” of scientific enlightenment in the New World. He writes,

“Largely through the enormous and enduring influence of Francis Bacon, the medieval identification of technology with transcendence now informed the emergent mentality of modernity.”

Similarly, in his book TechGnosis: Myth, Magic Mysticism in the Age of Information, Erik Davis observes, “As lodge members helped to imagine and construct our secular world, with its anticlerical embrace of science, technology and individual liberties, Masonic societies also served as the main channel whereby the ideas and psychology of gnostic occultism flowed into the heart of modernity.”30

Thus, two hundred years of building Dee’s esoteric Protestant empire upon Bacon’s Rosicrucian architecture culminated in the establishment of the Premier Grand Lodge of England in 1717, powering an international Masonic network as the machinery of revolution for the “Age of Reason” to advance the Kabbalistic goal of world repair.

For the next two hundred years, the Masonic conspiracy would guide world history to its next revolutionary milestone in 1917 with the British signing of the Balfour Declaration and the Judeo-Bolshevik revolution destroying the last Orthodox Christian empire in Russia.

The Esoteric Origins of Christian Zionism

By 1756, widespread millenarianism enabled the Sabbateans to merge with a new messianic movement led by Jacob Frank, who believed himself to be the reincarnation of Sabbatai Zevi. Although Poland acted as their central focus, the Frankists grew in London through the Masonic network centered around Rabbi Samuel Jacob Falk, the “Unknown Superior of the revolutionary Freemasons,” and creator of the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy against European Christendom.31

One European historian describes Falk as being “revered as a master of the holy names of God by mystical Jews and theosophical Christians, who sought his Kabbalistic instruction and assistance in medicine, alchemy, sexual magic, treasure-finding, lottery-predictions, and diplomatic intrigue.”32

Despite Falk having seemingly very little influence among the Jews, his renown as a Kabbalist, magician, and alchemist was widespread among esoteric Protestants, making him a John Dee-like figure of the eighteenth century. Along with Egyptian Rite Freemasonry, Falk inspired a crypto-Sabbatean cult of German Pietists known as the Moravians, who contributed greatly to the intersection of Jewish and Puritan communities across England.

This brand of German Pietism was developed by Immanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish mystic who, after being exposed to Kabbalistic ideas at Uppsala University, believed he talked with angels, similar to Dee. Swedenborg was also greatly influenced by Falk in his turning to occultism from a career as a scientist and inventor.

While in London, Swedenborg met with Falk where he “led a community of occultists comprised of Freemasons, Kabbalists, Rosicrucians, and Moravian Brethren that was later formally established as the Moravian Church in 1722 by Count Zinzendorf, which he later moved to Pennsylvania. As the pupil and grandson of Philipp Jakob Spener, the founder of Lutheran Pietism, Zinzendorf merged his connections between Rosicrucians and Freemasons to create his own secret society called the Order of the Grain of Mustard in 1722.33

Zinzendorf incorporated Kabbalah and Christian Theosophy into his blasphemous antinomian doctrines which emphasized meditating on the sexual organs of Christ and the deviant sexualization of both marital and pre-marital relations. Following in Zevi’s footsteps, Zinzendorf’s son Cristel also believed he was an embodiment of the messiah and “brought with him to London an antinomian tradition of homosexuality and sexual excess, hidden behind a veneer of spiritual enlightenment.”34 Although Christian philosemitism was unusual at the time, the Moravians inclusion of Judaism among their communities inspired a broader millenarian proto-Zionist movement among various Puritan sects.

Continuing the degenerate tradition of Sabbatean antinomianism, the Frankists practiced “salvation through sin,” believing that during the messianic age everything is permissible. This involved engaging in mass orgies, practices of sex magick, incest, and drunken debauchery among the cross-pollinated Jewish and Christian congregations. According to Scholem, Frank and his followers sought for “the annihilation of every religion and positive belief” and imagined “a general revolution that would sweep away the past in a single stroke so that the world might be rebuilt.”35

In 1776, two months prior to the Masonic founding fathers signing the American Declaration of Independence, Adam Weishaupt, a Jesuit educated converso, founded a quasi-Masonic secret society infamously known as the Illuminati. Nine years later, Jacob Frank mysteriously became very wealthy and moved his messianic cult to a suburb of Frankford, the home of Weishaupt and Mayer Amschel Rothschild.

According to Rabbi Marvin Antelman, in To Eliminate the Opiate, “it was the founder of the Rothschild dynasty who convinced Weishaupt to accept the Frankist doctrine, and who afterwards financed the Illuminati, with the aim of fulfilling the Frankist plot of subverting the world’s religions, or the Kabbalah’s Zionist objective of instituting a global government to be ruled by the expected Messiah.”36

By the mid-nineteenth century, Protestant Kabbalistic syncretism began to culminate in the first exclusively Christian Zionist cult known as the German Templers, who emerged from the esoteric Lutheran roots in Württemberg. Breaking away from Lutheranism in 1861, the Templers were a radical Pietist sect who believed themselves to be God's chosen people, tasked with rebuilding the Temple in Jerusalem and preparing for Christ's return.

Beginning in 1868, Templer families established agricultural colonies across Ottoman Palestine, including Haifa, Jerusalem's German Colony, and Sarona (later part of Tel Aviv), predating modern Jewish immigration by over a decade. Despite their early contributions to modernization and Zionist efforts, their alignment with Nazism in the 1930s led to internment and eventual expulsion by British authorities during World War II.37

The Dispensationalism Delusion

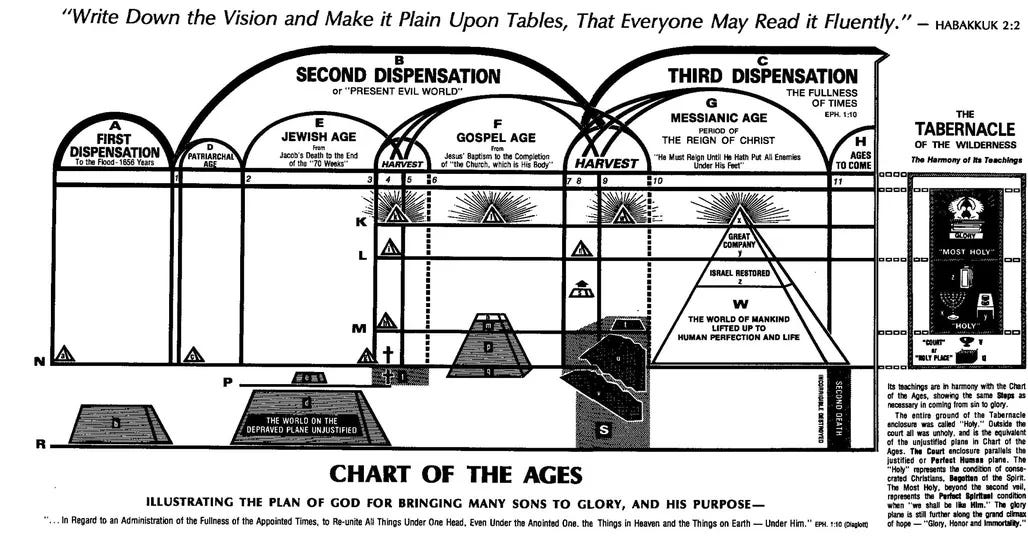

Apocalyptic speculation cemented itself further into the European Christian world by the early nineteenth century as end-times conferences and literature gained in popularity. This period saw the merging of millenarian futurist interpretations of Revelation and the increasing acceptance of esoteric charismatic ideas. Concepts such as the separation of the Church and Israel and emphasis on the “Great Tribulation” were also beginning to gain traction.

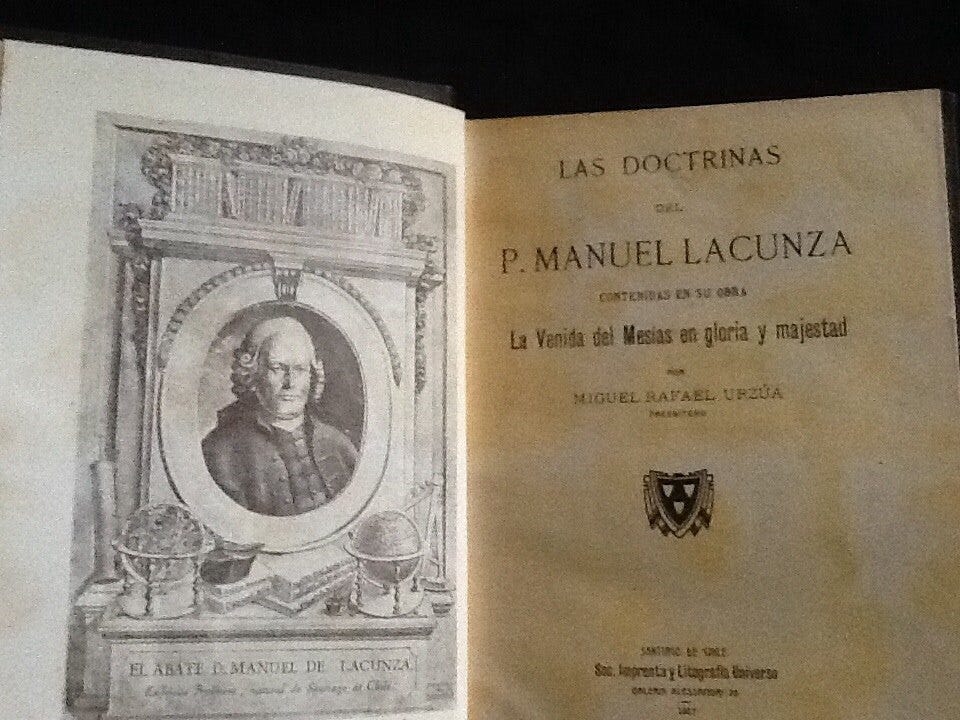

The doctrine of dispensationalism was first developed by a Marrano Jesuit priest Manuel Lacunza, whose book The Coming of the Messiah in Majesty and Glory played a major role in the Counter-Reformation to diminish the Protestant notion that the pope was the Antichrist.

The Jesuits were unsuccessful in their several attempts to introduce Lacunza’s new futurist system into Protestant eschatology throughout the nineteenth century until a Presbyterian pastor named Edward Irving read and translated Lacunza's book, which was written under the pseudonym of "Ben Ezra, A Converted Jew” to conceal his identity, “thus taking the heat off of Rome and making his writings more palatable to Protestant readers.”38

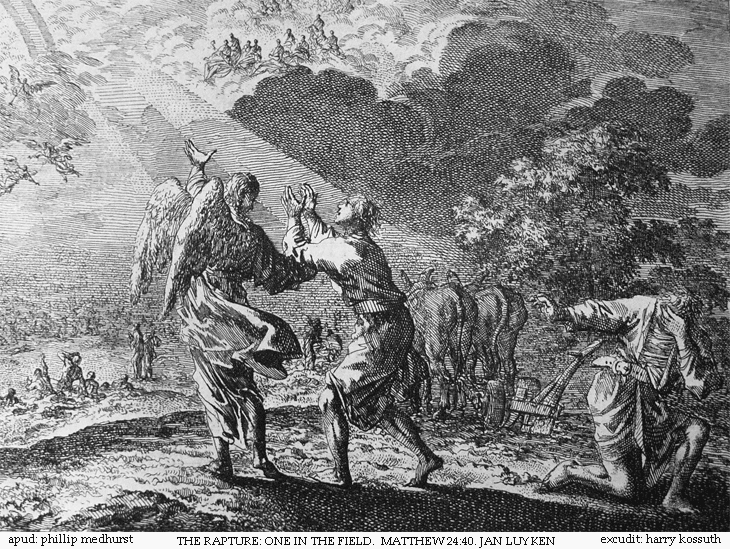

Irving’s adaptation of Lacunza’s futurism was then introduced to John Nelson Darby, founder of a Moravian sect in Dublin called the Plymouth Brethren, who further developed dispensationalism into a more comprehensive hermeneutic consisting of two distinct comings of Christ. One had a secret pre-tribulation rapture of believers, where Christ gathers Christians to secretly meet him in the air. Then a second rapture occurs seven years later when Christ saves the remnant of believing Jews and Christians during the persecutions of the Antichrist.

A key development in Darby’s dispensationalism came from Margaret Macdonald, a young Scottish woman who fell ill and experienced a vision of a pre-tribulation rapture in 1830, which she documented and shared with several Protestant ministers including Irving. Macdonald was involved in several occult practices such as charismatic speaking in tongues, automatic writing and levitation, to which Robert Norton wrote of her and a friend, “I have seen both her and Miss Margaret Macdonald stand like statues scarcely touching the ground, evidently supernaturally.”39

In 1861, a lawyer named Robert Baxter published Macdonald’s vision after becoming disillusioned with the Irvingites, proving her as the source of Darby’s new secret rapture doctrine. Despite the word “rapture” not appearing anywhere in the Bible or in the entirety of Church history prior to 1830, the rapture delusion cemented itself into evangelical consciousness as the great American myth.

At the core of Darby’s dispensationalist theology was the Theosophic notion that God requires human agents to advance the second coming, with their actions depending upon which dispensation of history is in effect. He even carefully introduced other Theosophic and Masonic synthesis into his translation of the Bible; referring to Jesus as the “coming one” (Antichrist), and God as the “Grand Architect."

One member of Darby’s “Plymouth Brethren” doomsday cult was the young Aleister Crowley,40 who was mystified by this new hyper-literal interpretation of Revelation and date-specific predictions of the rapture. In fact, Crowley derived his teaching on the aions of spiritual development from Darby’s dispensationalism, synthesizing it with the “angelic magic” of Edward Kelley and John Dee. Crowley also coincidentally “identified himself as the Antichrist as a necessary component of God’s dispensation to humanity during the final days.”41

In North America, millenarian sects spread throughout the northeast with the emergence of the Milliterite cult led by William Miller, a Freemason who began sharing his false predictions of an imminent second coming of Christ between 1843 and 1844.

After Miller’s prophecies failed, the Millerites dispersed and formed various millenarian sects, mainly as the Adventists. Charles Taze Russell, a Miller-influenced Adventist minister, would go on to form his own dispensationalist movement called the Watch Tower Society, which later adopted the name Jehovah’s Witnesses.

By 1879, Russell became the most prominent Christian Zionist of his time, teaching that “God's favor had been restored to Jews as the result of a prophetic "double" which had ended in 1878”42 and was also reported to have worked with the Rothschilds in the Zionist project.

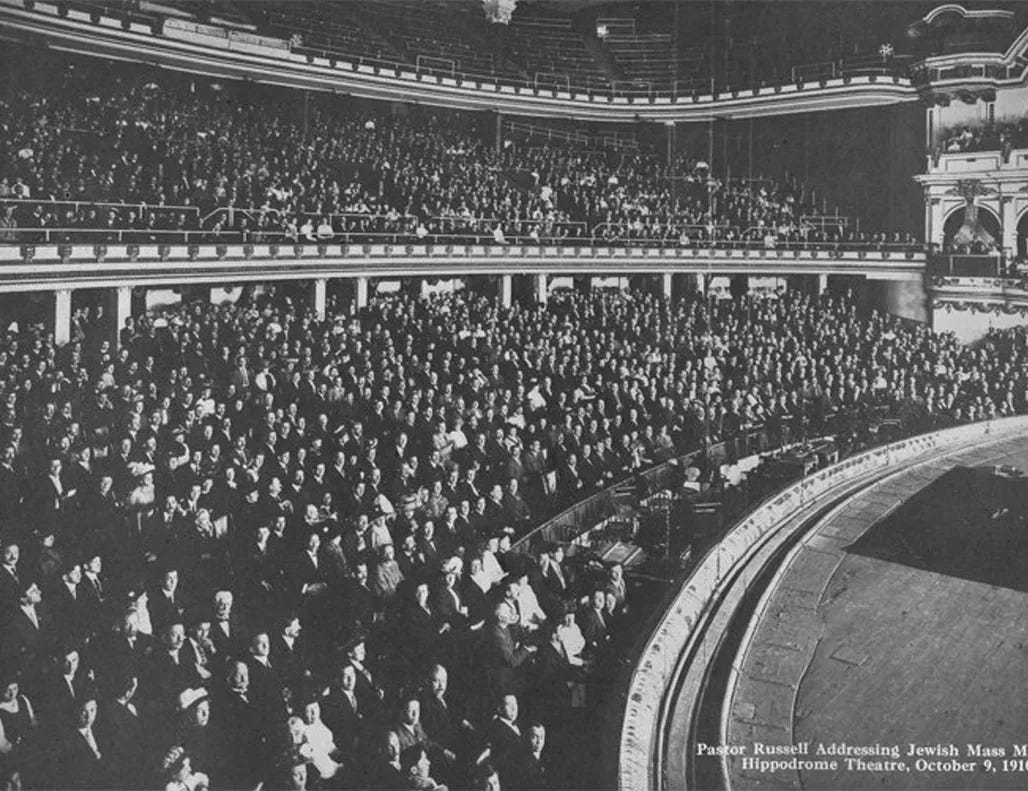

In 1910, Russell’s millenarian writings became the most widely distributed, privately published literature in the United States. In his rise to fame, Russell conducted a mass meeting at the Hippodrome, New York’s largest theater at the time, where he delivered a sermon titled Zionism in Prophecy on how God had a separate covenant with the Jews apart from the Christians; thus Jewish conversion to Christianity was not necessary in their divine calling back to rule as the center of God's Kingdom in Palestine. The New York American reported on that day:

The unusual spectacle of 4,000 Jews entastically applauding a Gentile preacher, after having listened to a sermon he addressed to them concerning their own religion. The mention of the name of a great leader [Herzl] who, the speaker declared, had been raised by God for the cause—brought a burst of applause.43

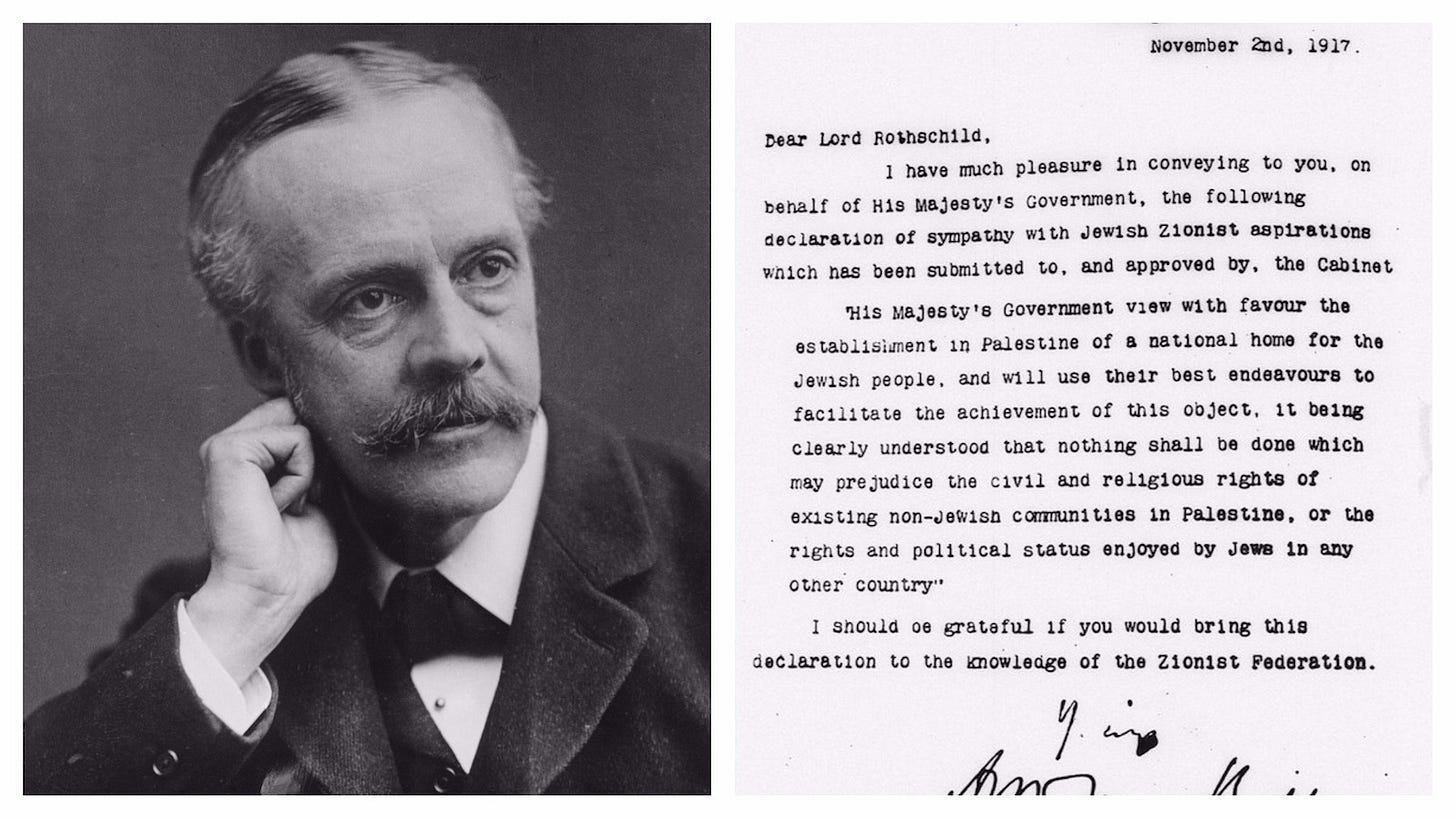

With dispensationalism as the final compelling argument for Zionism, British Protestant elites such as Lord Shaftesbury, Lord Palmerston, and Lord Balfour found justification for crafting the Balfour Declaration, fortifying Britain's commitment to creating the Jewish state of Israel. Lionel Walter Rothschild, head of the Rothschild family in Britain, eagerly endorsed this declaration. However, British support alone was insufficient, and American backing became even more crucial.

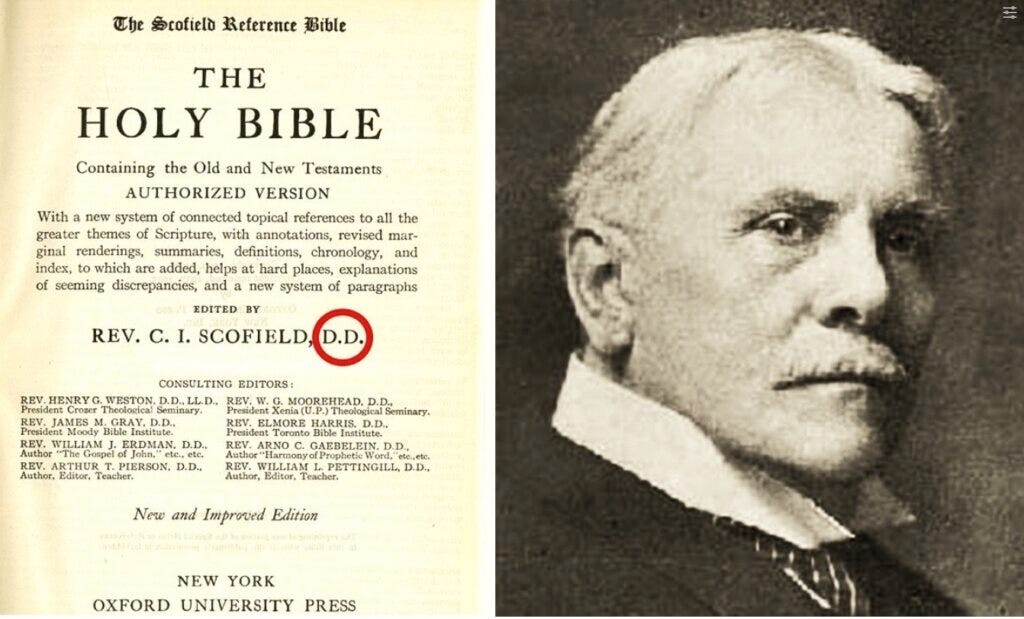

Scofield’s Talmudic Scam Goes Viral

After centuries of Protestant messianic fury, a satanic merging of secular Zionism and judaized Christianity unified in a ritualistic restoration of “divine sparks." To properly name this next revolutionary phase in world repair, Theodore Herzl officially coined the title “Christian Zionism” when he acknowledged the cooperation of key Protestant collaborators at the first Zionist Congress in 1897.44

In his manifesto titled Judenstaat, Herzl mentioned that he “saw antisemitism as a reality that could only be addressed by the territorial concentration of Jews in a Jewish state.”45 Seeking to materialize his vision, Herzl initially approached Edmond Rothschild to gain support for a Zionist takeover of Palestine, but was turned down since the Jews in Europe had already grown wealthy and powerful without a Jewish state.

But Herzl persisted in his efforts and later approached Pope Pius X in 1904, to which Pius declined, telling Herzl that “the Jews have not recognized our Lord; therefore, we cannot recognize the Jewish people.”

Herzl documented his papal appeal, lasting about twenty-five minutes and ending when he refused to kiss the hand of the pope, to which Pius responded by stuffing a pinch of snuff in his lip and sneezing into a red handkerchief.46 Five months later, Herzl died, but his Zionist plan began to gain significant traction after World War I when Winston Churchill saw a potential solution to both the Jewish question and their desire for influence in the Middle East.

Pius’s reaction reflected the sentiment towards a Jewish state among Christians in America. Protestant support would be crucial to this plan; but as history shows, this subversion would have to come from a gentile theologian to gain any credibility among American Christians.47

By the late nineteenth century, Darby’s dispensationalism became widespread in the English Protestant world, providing the framework needed for the European Zionists to imprint support for the Jewish fable of an earthly kingdom into American evangelical consciousness. Herzl’s utopian vision would finally start to materialize with the construction of an evangelical trojan horse to open the gates for a Jewish takeover of Palestine.

Another disciple of Darby, Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, was a crooked lawyer and former twice elected house representative in Kansas who later became a Congregationalist minister despite having no formal religious education. Scofield began frequenting the Lotos Club, where he met an incredibly wealthy Jew named Samuel Untermeyer, who played a significant role in establishing the Federal Reserve. Untermeyer financed Scofield's European travels, enabling him to meet with Zionists at Oxford University, which became a hub of Zionist activity funded by Lionel Walter Rothschild.

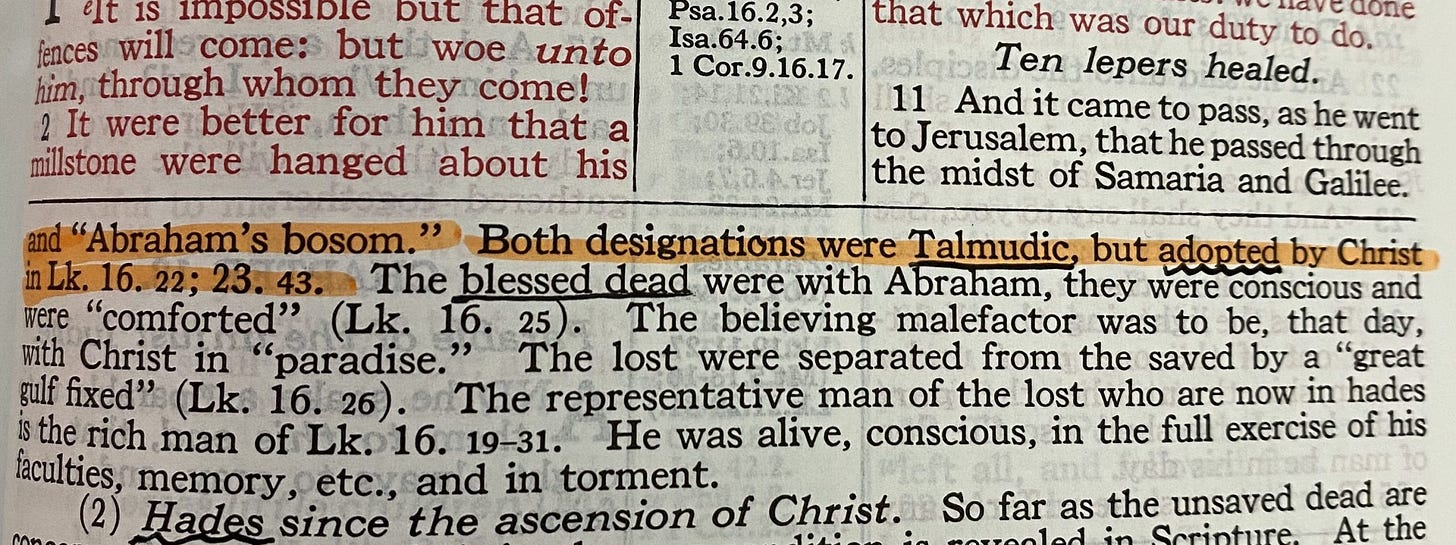

In 1904, Scofield relocated to the Masonic and covert banking hotbed of Switzerland to continue his work on the Scofield Reference Bible, the same location where the Rothschild funded World Zionist Congress was hosted. Three years later, Scofield completed his infamous Reference Bible riddled with dispensationalist eschatology masked as a fulfillment of Biblical prophecies. After several revisions, Oxford University Press published the main edition of the Scofield Reference Bible in 1917—the same year as the Balfour Declaration and four hundred year anniversary of the Protestant Reformation.

By the end of World War II, over two million Scofield Bibles were propagated through American Bible colleges, Protestant pulpits, and embedded in twentieth century evangelical theology, fueling the viral dispensational fury. Among the Reference Bible commentaries contained what would become the Christian Zionist mantra on Genesis 12:3 where Scofield noted:

‘I will bless them that bless thee.’ In fulfillment closely related to the next clause, ‘And curse him that curseth thee.’ Wonderfully fulfilled in the history of the dispersion. It has invariably fared ill with the people who have persecuted the Jew—well with those who have protected him. The future will still more remarkably prove this principle.

Contrary to popular belief, the Scofield Bible was actually owned by Oxford, not Scofield himself. As British foreign policy interests aligned with the developing state of Israel, Scofield's posthumous notes in the Bible became increasingly pro-Zionist over time. In the 1967 edition, the Genesis 12:3 commentary was revised to include the footnote: “For a nation to commit the sin of anti-semitism brings inevitable judgment.”

The word “antisemitism” was invented by a Jewish Zionist in 1860 named Moritz Steinschneider to promote the notion that the Jewish race is uniquely special thus required a special classification of bigotry, now effectively popularized in the pages of the Scofield Bible.

So the cycle repeats. The Rothschild’s weaponization of print technology dealt a major blow to the destruction of Christianity by distributing judaized Bibles into the hands of millions of American Protestants; just as the Jewish print tycoons did at the onset of the Reformation. As Zionism spread like wildfire among American evangelicals and political leaders, the Scofield Bible served as the final death blow to pursuade U.S. foreign policy towards supporting the Zionist takeover of Palestine.

The Jewish Messianic Age of Antichrist

“Zionists want to rule the earth. To achieve their ends, they use black magic and satanism. They regard satan-worship to gain the strength they need to carry out their plans. They want to rule the earth using satanic power.”48

—St. Paisios of Mount Athos

For the Kabbalists, hastening the conditions of the messianic age by inciting chaos is a justified means to the end of “world repair.” Through centuries of syncretizing revolutionary Kabbalistic doctrines with no ecclesiastical guardrails, Protestant millenarian cults and secret societies inadvertently served as a powerful vehicle for the Kabbalists to establish the gnostic architecture of their messianic utopia in establishing the Zionist state of Israel. It is no wonder why the proto-Zionist Heinrich Graetz declared a century prior that “the Protestant Reformation is the triumph of Judaism.”49

Louv notes that Israel’s founder and first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, described the Zionist state as a “magnificent, messianic enterprise.”50 He adds that “Abraham Kook, the first chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine, studied Kabbalah and Hegelian philosophy, concluding that God had used all of history to divinely conspire to return the Jews to Palestine, and that he had even used the actions of pagans and apparent opposition and persecution of the Jews to do so.”51 As one Israeli news source confidently stated:

Christians are realizing that the Bible is a work that’s all about the Jewish people in the Land of Israel and it’s taken a long time for this all to crystalize…there are spiritual tectonic shifts of historic magnitude happening both within the Jewish people as well as the world around us…One of the most shocking and curious of these shifts is happening within Christianity, as hundreds of thousands of Christians around the world are connecting to the Jewish roots of their faith, keeping many of the Biblical holidays, Torah commandments, and Jewish rituals.52

The transmission of the Kabbalistic spirit increasingly depends upon technology as a tool to achieve its chiliastic goals in the modern world. Without the cryptographic potential of the printing press, the necessary preconditions for the infrastructure and mass proliferation of secret societies to advance the Kabbalistic goal of tikkun would not have been possible.

In this regard, the rabbis of Kabbalah tell us how the self-fulfilling prophecies of the Zohar are defined by the instrumental role technology plays in the final redemption of the messianic era of tikkun:

In a sentence, one may summarize the Zohar by saying that science and religion will converge. As time goes on, science will reveal the profound secrets of creation as already described in the mystical tradition, and it will provide the technological means for all to access that information.53

Charles A. Kroloff, a Reform rabbi of Lurianic Kabbalah, describes how this technological Zionist utopia is actualizing in what calls “The New Zionism,” which is:

“Based on a global economy that rewards innovation in technology, especially in health care, environment, security, and communication (software for your voicemail was developed in Israel). Israeli brainpower and entrepreneurial spirit provide a new foundation for building a prosperous and hopefully secure Israel.54

Another writer for The Times of Israel clearly states the ideal humanistic vision of the Zionist project:

Zionism is the quintessential humanist quest. It is about improving life and living standards. It is about eradicating hatred and intolerance and not allowing exogenous forces to dictate one’s lifestyle. It is about taking back what was once taken away and stating with confidence and with integrity that it will never be taken again away.55

In his controversial book The Jewish Utopia, Talmudic scholar Dr. Michael Higger reveals a carefully examined rabbinical consensus on the characteristics of what he calls the “new state of the nature of man” that will usher in the “ideal messianic age." One prominent theme is that enlightenment will play a major role in what he calls “the general spirit of the new age,”56 which he ascribes to a necessary preparation for the coming Jewish messiah:

Jerusalem will become the ideal capital of the new Universal State…Hence, with the advent of the Messiah, who will usher in the ideal era, all the national ensigns and laws, which are barriers to genuine international peace, brotherhood, and the happiness of mankind, will gradually disappear…57

Only the Messianic flag, the symbol of knowledge, peace, tranquility of the individual mind, will remain, and all the nations will center round that emblem…All will recognize one flag or standard, bearing the name of God…The world will, therefore, unite in praising the Lord for Israel’s universalism.58

Once again, these terms like knowledge, peace, and unity, are encoded with a Jewish mystical meaning to usher in the age of Antichrist through the convergence of humanistic enlightenment with science and technology. And to further understand what this messianic age looks like, Gershom Scholem uncovers some of the esoteric language describing the apocalyptic events prophesied in the Zohar as a “gradual illumination of the world by the light of Messiah” that culminates in a mystic utopia:59

At the time when the Holy One, blessed be He, shall set Israel upright and bring them up out of Galut He will open to them a small and scant window of light, and then He will open another that is larger, until He will open to the them the portals on high to the four directions of the universe…so shall it be and not at a single instant…the primary work of tikkun – the repair of the world – is dependent on the Jewish sages ascending the Sefirot tree so they can transmit the knowledge of the kingdom of God to the nations of the world.60

Kabbalistic Chaos and The Ark of Salvation

It should be understood that the Sefirot (tree of life) in Lurianic Kabbalah is a gnostic inversion of the Eucharist in Orthodox Christianity, which the Holy Fathers such as St. Gregory the Theologian and St. Ephrem the Syrian consider a representation of Christ Himself. As partakers in the Life-Giving Eucharist, we experience a unification with Christ in a way that Adam and Eve never encountered since they chose the forbidden fruit of esoteric gnosis and were consequentially expelled from paradise by God.

Conversely, the Zohar teaches the ultimate Jewish chutzpah that it was actually Adam who expelled God from the garden, separating man from the Kabbalistic goddess Shekinah, which was fully manifest in Eden. It is not difficult to see how Kabbalists justify their belief that collective human action can also hasten the conditions to restore a messianic kingdom on earth; and how Protestant sects were used as a vehicle to accelerate Kabbalistic world repair.

Yet, the evil forces of revolution cannot actually create anything; they can only chaotically rearrange the Christian order to impose their utopian ideology in an effort to re-unify their destruction. So is the case for the false gods of Judaism and its heresies.

In the Kabbalists’ effort to reshape reality itself, they are limited to imposing their absence of reality by distorting the Truth. In the face of evil, Father Elpidios Vagianakis encourages us that “God plans to disrupt the machinations of the devil through a Great Reset of His own within the Church.”61

The Kingdom of God is present in the Orthodox Church and fully realized when Christ returns to transfigure the entire created order in His timing and not ours. Our Lord promised us that the gates of hell would not prevail against His Church, the True Israel, which will remain uncorrupted by the spirit of the age and continues to preserve and transmit Truth. It is our duty as Orthodox Christians to actively participate in the only true revolution against the spirit of the age.

Have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness,

but rather expose them.

Ephesians 5:11

Hieromonk Job (Gumerov). What is Kabbalah? / Orthodoxy.Ru. 2016. https://pravoslavie.ru/6905.html

Louv, Jason. 2018. John Dee and the Empire of Angels: Enochian Magick and the Occult Roots of the Modern World. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions. 330

Ibid.

Ibid.

Livingstone, David. 2015. Transhumanism: The History of a Dangerous Idea. S.l.: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 27.

Louv, 34.

Newman, Louis I. 1925. Jewish Influence in Christian Reform Movements. New edition. Place of publication not identified: Columbia University Press. 528.

Livingstone, 28. (Cited from: Douglas, Lord Alfred. 1921. Plain English. North British Publishing Company.)

Ibid. (Cited from: Samuel Butler, Hudibras, note to pt. 1, canto I, 527–544; Paul Benbridge, "The Rosicrucian Resurgence at the Court of Cromwell," in The Rosicrucian Enlightenment Revisited. Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press. 225.)

“The Hartlib Papers.” 2025. Dhi.ac.uk. 2025. https://www.dhi.ac.uk/hartlib/.

Livingstone, 29.

Goldish, Matt D., and Richard H. Popkin, eds. 2001. Millenarianism and Messianism in Early Modern European Culture. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2278-0. 93.

Ibid.

Livingstone., 30.

Robert Sepehr, dir. 2022. 1666 and the Dark Messiah Sabbatai Zevi - ROBERT SEPEHR.

Curtis, Rodney M. 2022. “Moravians in London 1740-1790. Merging Judaism and Christianity. Sabbatianism and Frankism.” https://www.academia.edu/81907447

Popkin, Richard H. and Weiner, Gordon M. 1994. Jewish Christians and Christian Jews from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Dordrecht: Springer. 57-60.

Ibid, 92.

Ibid.

Liagre, Guy. n.d. Protestantism and Freemasonry. (cited in: Bogdan, Henrik & Snoek, Jan A.M. 2014. Handbook of Freemasonry. Leiden. 164)

Liagre, p.165

Rose, Fr Seraphim. 1975. The Orthodox Survival Course. 2nd Edition (Draft Copy). Samizdat Press. 17.

Popovich, Justin, and Asterios Gerostergios. 1997. Orthodox Faith and Life in Christ. 1st ed., Nachdr. Belmont, Mass: Inst. for Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 90.

Pike, Albert. Morals & Dogma. 1871. 30-31. (cited in: Witcoff, Michael. 2025. On the Masons and Their Lies: What Every Christian Needs To Know. 3rd ed. Self-published. 73.)

Jones, E. Michael. 2008. The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and its Impact on World History (Selections, Taken from "Culture Wars" articles). Fidelity Press. South Bend: IN. 210.

Levi, Eliphas. 1922. "The History of Magic." 2nd Edition. William Rider & Son. London. 382.

Poncins, Vicomte Leon De. 2015. Freemasonry and Judaism: Secret Powers Behind Revolution. EWorld, Inc. 18.

Ibid., 107 (Cited from Noble, David F. 1999. The Religion of Technology: The Divinity of Man and the Spirit of Invention. Penguin Publishing Group.)

Ibid.

Ibid.

Goldish and Popkin, xix.

Ibid.

Livingstone, 36. (Christian Kabbalism took root in German Pietist communities in Württemberg during the seventeenth century, tracing its Kabbalistic origins to Jakob Böhme. After embracing Lutheranism in 1534, Württemberg became a haven for the esotericism and anti-modern religious movements, maintaining this environment well into the 1800s. Württemberg was home of Hegel, Reuchlin and later the proto-Zionist sect known as the German Templars; all of whom were influenced by Kabbalah.)

Curtis, 1.

Livingstone, 40. (Citing: Antelman, To Eliminate the Opiate.)

“Weishaupt and Rothschild - New World Order University Forum.” New World Order University Forum, 31 Aug. 2017, newworldorderuniversity.com/weishaupt-and-rothschild/

Shefer-Vanson, Dorothea. 2014. “Templers, Germans and Nazis.” the Jerusalem Post | JPost.com . The Jerusalem Post. October 22, 2014. https://www.jpost.com/blogs/from-dorotheas-desktop/templers-germans-and-nazis-379471.

Hendrie, Edward. 2001. Solving the Mystery of Babylon the Great. Great Mountain Publishing. Shady Cove: OR. 255.

Fahy, Paul. 1997. The Origins of Dispensationalism. Understanding Ministries.

“Chapter 1 - the Confessions of Aleister Crowley - the Libri of Aleister Crowley - Hermetic Library.” 2017. Hermetic.com. 2017. https://hermetic.com/crowley/confessions/chapter1.

Louv, 22.

Wikipedia contributors, “Charles Taze Russell,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Charles_Taze_Russell&oldid=1280139446

Phillipe, Bohstrom. “Before Herzl, There Was Pastor Russell: A Neglected Chapter of Zionism” Haaretz, May 2023, archive.is/5y4Hu#selection-2437.0-2437.219.

“A History of Christian Zionism | Israel Answers.” 2020. Israelanswers.com. 2020. https://www.israelanswers.com/christian_zionism/a_history_of_christian_zionism.

Wikipedia contributors, "Zionism," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Zionism&oldid=1278406173

Herzl, Theodor. “THEODOR HERZL: Audience with Pope Pius X (1904).” Ccjr.us, 26 Jan. 1904, ccjr.us/dialogika-resources/primary-texts-from-the-history-of-the-relationship/herzl1904.

Loper, Deanne M. 2019. Kabbalah Secrets Christians Need to Know: An In Depth Study of the Kosher Pig and the Gods of Jewish Mysticism. Independently published. 128.

“The Prophecies of St Paisios of Mount Athos |.” 2015. Orthodoxaustralia.org. 2015. http://orthodoxaustralia.org/2015/12/01/the-prophecies-of-st-paisios-of-mount-athos/. (Full article can be read on The Reversion - https://thereversion.co/p/elder-paisios-against-zionists-and)

Graetz, Heinrich. 1894. The History of the Jews. Vol. II. The Jewish Publication Society of America. Philadelphia. p.67. Cited in Jones, p.297.

Louv, 28-29.

Ibid., 29.

Adler, Rivkah Lambert. 2016. “How Christians Embracing Torah Could Signal Ultimate Redemption.” Israel365 News. September 9, 2016. https://israel365news.com/310336/christians-striving-live-biblically-oriented-lives/.

”Chabad.org. 2006. “Mashiach.” @Chabad. February 27, 2006. https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/361881/jewish/Mashiach.htm.

“The New Zionism: Driven by Innovation in Technology.” 2025. Reform Judaism. January 2, 2025. https://reformjudaism.org/blog/new-zionism-driven-innovation-technology.

Eton Ziner-Cohen. 2015. “The Blogs: Zionism Is Humanism.” Timesofisrael.com. 2015. https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/zionism-is-humanism/.

Higger, Michael. 1932. The Jewish Utopia. CPA Books Inc. 105-106.

Ibid., 114.

Higger, 42.

Loper, Deanne M. 2019. Kabbalah Secrets Christians Need to Know: An In Depth Study of the Kosher Pig and the Gods of Jewish Mysticism. Independently published. 84.

Scholem, Gershom. 1971. The Messianic Idea in Judaism. New York, NY: Shocken Books, Inc. 39-40. (Cited in: Loper, 84.)

“GREAT CHRISTIAN RESET.” Brighteon.com, 2021, www.brighteon.com/watch/a025c7d6-a07e-42a4-8479-084e0fbc8f0d?index=31.

I subbed to help you do the research you want, but id like to see as much on this subject as you are willing to do. Incredibly important. Thank you.

Epic!