Read Time: 25 minutes

Authors Note: This article is part one of an ongoing series on the esoteric spirit of the modern west. I will be publishing an upcoming book which contains a much deeper dive into this subject.

Read Part II:

Introduction

It is a fundamental mistake to think of the Protestant Reformation as a mere rebellion against the corruption of the Roman papacy. The Reformation is an ongoing Kabbalistic revolution that has fragmented Christendom into thousands of pieces—imposing the worst catastrophe upon Western civilization. It led to the destruction of Christian tradition, the birth of Freemasonry, the spread of nominalism, and the creation of the antichrist Zionist state.

However, it is also a mistake to think of Kabbalah as mere mystical Jewish teachings. Kabbalah is a collection of revolutionary esoteric political doctrines to “repair the world” and establish both a spiritual and material Jewish utopia. An admission of this can be found in the words of Dr. Michael Laitman, host of the largest Kabbalah website in the world, where he states:

The wisdom of Kabbalah, as defined by the greatest Kabbalists, is a method to correct man and the world…

If Kabbalah will spread amongst people, then we will avoid all the catastrophes, we will merit both this world and the world to come, and both of these worlds will unite into one…Only the dissemination of Kabbalah will save the world.1

Achieving world repair, known as Tikkun Olam, is the primary aim of Kabbalah. It is a universal revolutionary blueprint to overthrow the Christian order by rearranging the material world through the magic of social engineering, technology and institutional control. This alchemical transmutation of mankind into a new “primal man,” known in Kabbalah as Adam Kadmon, is the manifestation of the Antichrist, created through the merging of opposing forces and systematic revolution. As the world's preeminent scholar of Kabbalah, Gershom Scholem, notes:

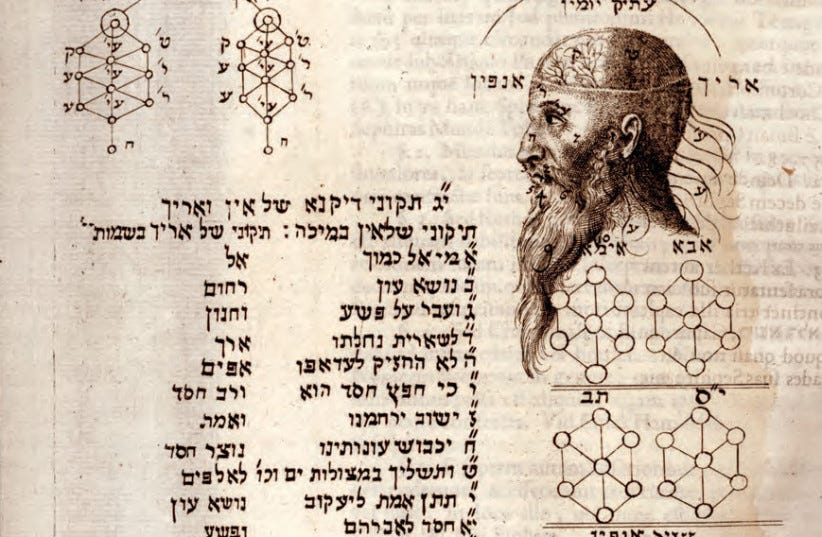

From the dust of this cosmic catastrophe the universe is reconstructed through the Primordial Adam Kadmon, who is the creator of the earthly Adam. From Ein Sof, “healing, constructive lights” go forth from the forehead of Adam Kadmon.2

After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70AD, the Jews were scattered from Palestine and found their new textual architecture in the form of the written word. According to the Sefer Yitzrah, the “Book of Creation” in Kabbalah, the numbers and spheres of the ten Sefirot “constitute a kind of cosmic DNA code.”3 This represents the framework of the Kabbalistic understanding of reality, with the Sefirot as a skeleton of the universe that shapes the creation of this new man in the construction of the Jewish messianic kingdom of the antichrist.

Jewish influence is inseparable from revolutionary movements and heresies in the Christian world; and the religious anarchy of Protestantism provided a fertile soil for it to take root. The Protestant movement is the longest lasting revolution in world history, advancing history itself towards the end of the age.

In this article, I will uncover some prominent themes, figures, historical events and doctrines in which the inner esoteric spirit of the Protestant revolution has transmitted and contributed to the mystical reshaping of Western civilization and humanity.

The Revolution Will Be Judaized

Like all ancient Christian heresies, judaizing never dissolved, but continued its transmission in new forms throughout history. The early Church Fathers strongly condemned the judaizers of their time, notably seen in St. Ignatius of Antioch’s letter to the Magnesians, where he declared, “It is absurd to profess Christ Jesus, and to judaize. For Christianity did not embrace Judaism, but Judaism Christianity, that so every tongue which believeth might be gathered together to God.”4

Nearly a century before Luther’s Reformation, the Jewish financed Hussite revolution led by Jan Hus, gained cooperation with the Jews in Bohemia due to their shared affinity with Judaism and undermining the authority of the Catholic Church.5 In fact, the Hussites were among the first sectarian movements to practice Sola Scriptura and strongly oppose the veneration of saints.

Hus was eventually burned at the stake by secular authorities after the Council of Constance declared him a heretic, but his teachings would later influence Luther, who even wrote prefaces to a number of Hus's works. To this, Newman concludes that “the Hussite Reformation from its inception to its decline bore marks of Jewish and particularly Old Testament influence.”6

By 1517, the Jews who controlled the spice trade began reinvesting their profits into the printing industry, quickly weaponizing print technology as a profitable means of subverting the Reformation.7 Their secret trafficking of unauthorized and heretical biblical translations helped them gain a significant advantage in the war with Spain while promoting the Reformation and weakening the hegemony of the Roman Catholic Church.

It is no coincidence that the Reformation emerged while the Medici banking family, who funded the Renaissance, simultaneously introduced Hermetic and Jewish esoteric literature into classical learning.8 The Renaissance thus birthed a new syncretic religion of Christian Kabbalah which began to flourish in the late 15th century, championed by Catholic humanist Johann Reuchlin and Italian proto-Protestant Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

Both Reuchlin and Pico were so deeply entrenched in Kabbalah that any degree of influence they transmitted should be understood as Kabbalistic, whether direct or indirect. E. Michael Jones writes on the very danger in this transmission:

Christianity enabled Reuchlin to derive from Kabbalah a universal esoteric science which incorporated pagan, Jewish, and Christian elements, but once that esoteric science was derived, it threatened to replace Christianity as the true religion.9

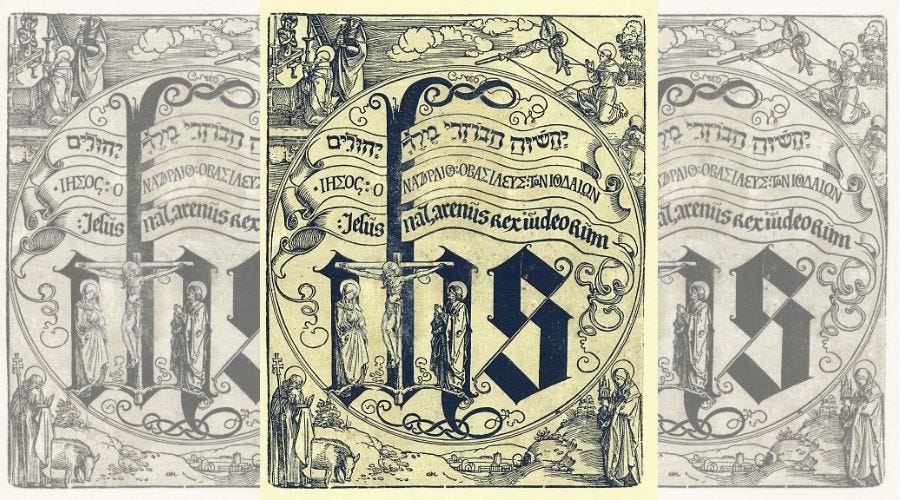

Christian Kabbalists were drawn to the Jewish esoteric notion that Hebrew is a divine language possessing inherent mystical power; the tongue through which God created existence, communicated with Moses, and engaged with celestial beings. But they also saw it as a means of legitimizing Christianity, tying it to an esoteric Renaissance tradition called prisca theologia, which is the belief that the most ancient theology is the truest.10

Renaissance historian Frances Yates maintains that Christian Kabbalah should be understood as a euphemism for judaizing Protestantism, adding:

Christian Kabbalah was not a recapitulation of the Jewish tradition, but its creative re-molding, a metamorphosis engendered by newly aroused religion-making vision. Though it would be too bold to judge Gnosticism a legitimate historical parent, this movement was arguably encouraged and fostered by distant transmissions and legacies of the old heresy.11

Considering Yates specialized in esoteric studies, the language she used here was almost certainly intentional. This “creative re-molding” is a Kabbalistic manipulation of Christianity through ritual magic to reshape the material world, which manifests in the internal nature and external transmission of Protestant thought in the following two ways. First, in the internal emphasis on salvation as an alchemical process of self-enlightenment through the transmutation of a new man. Second, as external actions to hasten eschatological events by replacing the old Christian order with a new messianic Jewish kingdom on earth.

While the Christian Kabbalists sought to legitimize Christian doctrine looking back through prisca theologia, Christian Hebraists such as the Hussites looked forward by studying Jewish texts and rabbinical traditions as part of an eschatological mission to convert Jews to Christianity. Yet, even in the Hebraist’s application of seemingly non-mystical rabbinical texts contains an esoteric Jewish understanding of reality, which likely played no small role in Philip Walsh’s claim that “the Reformation drew its lifeblood from rational Hebraism.”12

One Hebraist who all three primary reformers shared a common influence from was a well known converso and Franciscan monk named Nicholas of Lyra. Zwingli especially had several Hebraist colleagues, including his teacher Jacob Ceporinus, a former student of Reuchlin. According to Newman, “From Pico, it is certain that Zwingli borrowed considerably”13 to describe numerous mysteries in the Old Testament, such as his Kabbalistic application of the "Ineffable Name.”

It’s safe to say Yates is correct in stating that this remolding of Christianity is nothing more than a new manifestation of the ancient judaizing heresy. But with the power of a new technology, Gutenberg’s information machine would accelerate the spread of this ancient heresy at an unprecedented rate, sparking the Reformation as the first viral movement in history.

Luther’s Esoteric Revolt and the Alchemy of Sola Scriptura

While Luther rightly opposed to the “Kabbalistic foolishness” of his contemporaries and later wrote the infamous polemic On the Jews and Their Lies, in his Commentary on Galatians, he referred to his newly conceived doctrine of justification by faith alone (sola fide) as “true Cabala.”14 Luther was not referring to the teachings of Kabbalah here, but the acknowledgement tells of the hermeneutical trend of Hebraism established by Reuchlin to “unlock the mysteries of the Scriptures.”

Nevertheless, in light of Luther’s sola fide doctrine, it is interesting to see how over time it developed into a kind of Kabbalistic ritual magic among modern evangelicals to make a mere profession of faith and be saved; as if the words themselves contain an inherent mystical power to regenerate the individual by simply speaking them.

Another notable esoteric influence in the development of Luther’s theology can be seen in his writings where he referred to prisca theologia and mentioned alchemy as symbolic of the Christian resurrection of the dead:

The science of alchemy I like very well, and, indeed, 'tis the philosophy of the ancients. I like it not only for the profits it brings in melting metals, in decocting, preparing, extracting, and distilling herbs, roots; I like it also for the sake of the allegory and secret signification, which is exceedingly fine, touching the resurrection of the dead at the last day.15

The doctrine of Sola Scriptura implies the Kabbalistic notion that the Scriptures are alchemically encoded with mystical wisdom, which can only be decoded by the individual interpreter acting as the “key” to unlock their true meaning.16 Moshe Idel is among many Jewish philosophers to point to this notion in describing Kabbalah as “the keys sacrosanct, even in the eyes of the Jew, that could unlock the gates of the mysteries of the Scriptures, demonstrating Christian truths using Jewish rules.”17

Likely due to mere coincidence, it is at least interesting that a similar metaphor was used by Fr. Seraphim Rose to describe Luther’s new normative authority of biblical interpretation, observing that:

“It opened the gate to total subjectivism in religion. And thereupon he gives us a key also to today because this same principle, the individual —whatever I believe, whatever I think has a right to be heard — then becomes the standard. He himself finally achieved some kind of dogmatic system and tried to force it on his followers. But the very idea which he fought for was that each individual can interpret for himself; and therefore from him come sects.”18

The spawning of new sectarian movements was also a result of Luther turning the Protestant churches into Talmudic debate halls, as Jones writes, “with evangelical theologians acting as rabbis” arguing over biblical interpretations. He adds that Luther, although outspoken against the other judaizing reformers, “consulted rabbis to construct his text, and that text was, therefore, skewed in favor of judaizing.”19

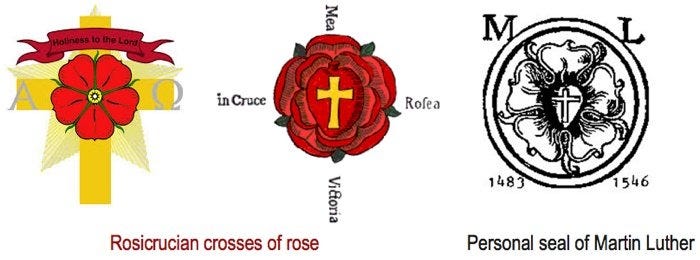

By 1534, Lutheranism had won over Reuchlin’s birthplace of Württemberg while it was flourishing with Hermeticism, culminating in the Rosicrucian Order; the symbolism of the rose and cross is likely due to the influence of Lutheranism on Rosicrucianism. Most Rechulinites later became Lutherans, and “the flame that Reuchlin kindled, Luther fanned into a raging inferno in which the Talmud and the Reformation were merged into each other.”20 David Walsh writes that during this era:

The influence of the Enlightenment, to the extent it had made itself felt in Württemberg, was integrated with a theosophic philosophy of nature and a speculative pietism which was concerned with the progressive revelation of the divine structure of history.21

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Württemberg continued to be a central hub for the esoteric tradition, described by Justinus Kerner as "the homeland of haunted and spectral doings" and "a very goblin's nest" due to its narrow valleys and old castles.22 Hermeticism profoundly influenced G.W.F. Hegel, another Württemberg native, who developed connections with the Freemasons and Rosicrucians. Philosopher Glenn Magee notes that “some of the more famous claims of Hegel's historical dialectic are to be found in the Kabbalist and Joachimite mystical traditions.”23

Following Luther’s revolution, the esoteric tradition in Württemberg maintained a long and rich history spanning several centuries, still present today. Such is the case for the various societal transformations that occurred wherever revolutionary Protestant activity flourished.

The Death of the Old Order and Rise of the New Gods

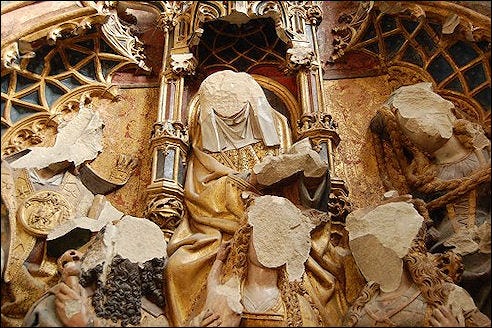

Every anti-Christian revolution throughout modern history included some form of iconoclastic destruction in its wake. The Jacobins, the Judeo-Bolsheviks, the Spanish anarchists; all carried out the physical destruction of the old Christian order to construct their new chiliastic vision. The Protestant revolution was certainly no exception. Yet, because of the inherently sectarian nature of Protestantism, iconoclasm was opposed by Lutherans while violently carried out by the Zwinglians and Calvinists throughout parts of Europe.

Out of the main three Protestant reformers, the Swiss theologian Ulrich Zwingli was the most educated in Hebraic studies. As it turns out, Zwingli’s sect was also the most aggressively iconoclastic. Newman confirms the Judaic influence of Zwingli’s iconoclasm in the reformer’s own words: “The Jews do not carry images, neither do the Zwinglians nor Calvinists.”24 It is no mystery that Zwingli’s iconoclastic zeal derives from his obsession with rabbinical thought; for which Luther and many Swiss Catholics rightly labeled him a judaizing heretic.

It’s quite common even among Protestant historians to describe the iconoclastic revolt with the recurring language of the “old order” being destroyed. Here Philip Schaff includes how Zwingli was true to his principles of Reformation and not even the cross of Christ was exempt from the iconoclastic fury:

”The old order of worship had to be abolished before the new order could be introduced. The destruction was radical, but orderly…the churches of the city were purged of pictures, relics, crucifixes, altars, candles, and all ornaments, the frescoes effaced, and the walls whitewashed so that nothing remained but the bare building to be filled by a worshiping congregation.25

On paper, Calvin took a less rigorous approach to the abolition of holy images. While he strongly opposed the inclusion of holy images in Protestant worship, even calling the depiction of the cross an abomination,26 he did not explicitly advocate for iconoclasm and instead encouraged a more peaceful removal of Christian images. However, the Calvinists justified their violent iconoclastic crusades of 1566 with Calvin’s doctrines and were never explicitly condemned by the reformer.

It is commendable that Luther, in this regard, opposed such extreme iconoclasm. Why then, was the destruction of Christian images not held as a consensus position among all three reformers, despite their mutual appeal to a clear reading of Scripture? Perhaps for Zwingli and Calvin, the clarity of Scriptures came not from a clear reading of Exodus 20:4, which does not detail what constitutes a graven image, but from the Babylonian Talmud which does clarify: “It is forbidden to make complete solid or raised images of people or angels, or any images of heavenly bodies except for purposes of study.”27

The iconoclastic fury of the Calvinists represents not only a material abolishment of the old Christian order, but the establishment of a new order where the individual is the new god. In the words of Fr. Seraphim Rose:

This is the meaning of Humanism and Protestantism: get rid of the religious tradition, the Orthodox tradition so that the new god can be born... just as the individual god is being born also the world now becomes divine.28

The New American Religion of Puritan Kabbalah

From the moment the pilgrims arrived in New England, Kabbalah began to make its way through academic institutions and Puritan congregations, laying the foundation of a new mystical American ethos. Despite the colonial Jewish population being minuscule, Kabbalah had such a profound impact on the early founders that Ogren claims it to be the “fabric of American Protestantism.”29

Historian D. Michael Quinn also supports the notion that esoteric studies were flourishing among early American institutional leaders, claiming:

Many of New England’s practicing alchemists were Yale and Harvard graduates who continued their experiments into the 1820s. These alchemists served as chief justice of Massachusetts, president of the Massachusetts Medical Society, president of Yale College, and president of the Connecticut Medical Society.30

Kabbalistic thought in America spread through several key figures, including renowned Puritan minister and Harvard president Increase Mather, along with his son Cotton. The elder Mather's interest in Jewish mysticism was particularly sparked by the Sabbatean movement led by Sabbatai Zevi in the 1660s, which was largely responsible for transmitting Lurianic Kabbalah throughout Europe. Cotton Mather even went on to develop the teaching that Native Americans were of Jewish ancestry, an idea so influential it later became a core doctrine of Mormon theology.

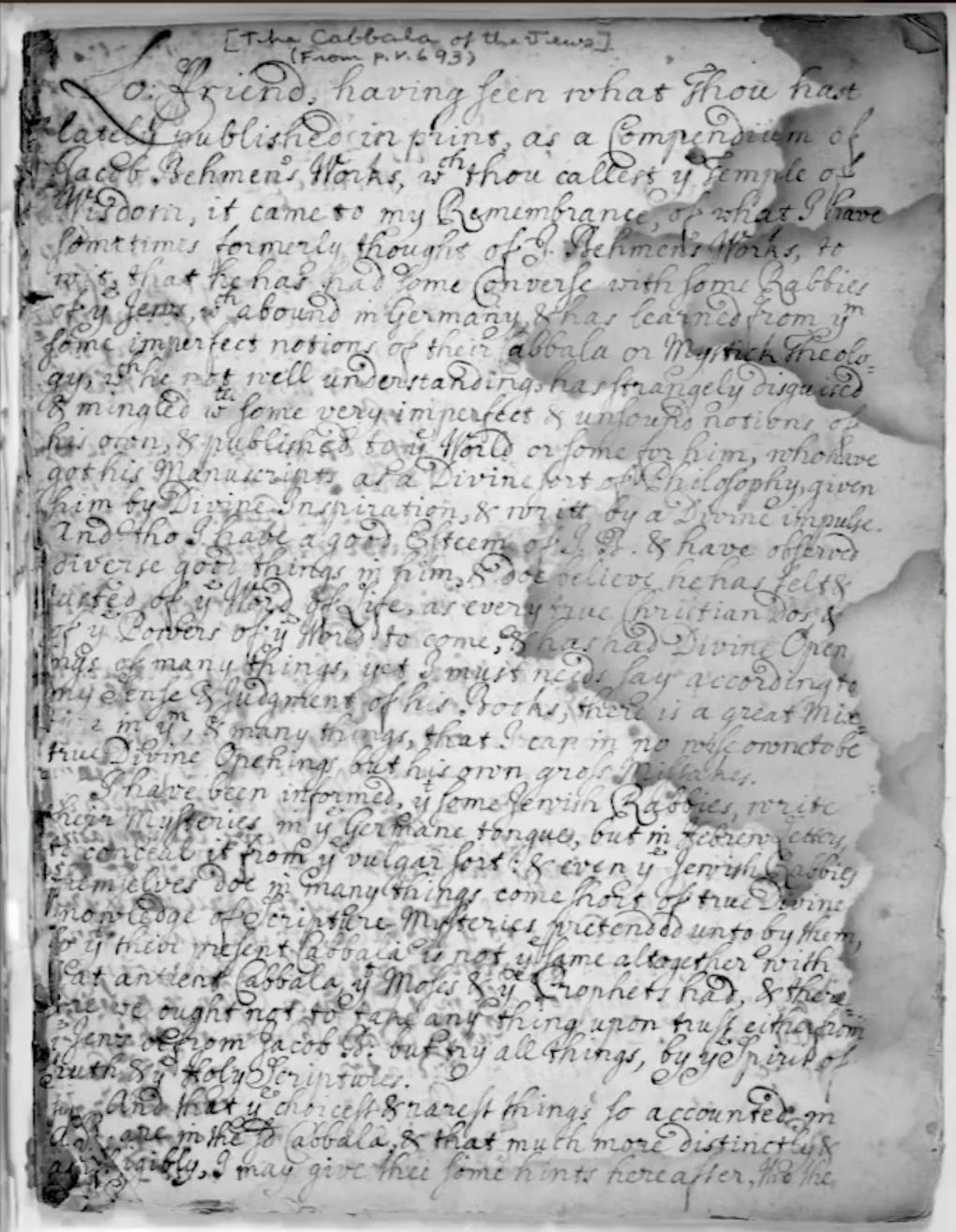

The first American Kabbalistic manuscript was written in 1688, titled The Cabala of the Jews, authored by the Scottish Quaker George Keith. The manuscript revealed that Keith had been deeply influenced by Christian Kabbalists in England, particularly through his association with the Cambridge platonist Anne Conway and her circle at Ragley Hall. Keith’s manuscript eventually made its way into the Mather family papers, demonstrating how Kabbalistic ideas circulated among colonial America's religious elite.

Oddly enough, Keith’s manuscript was written as a polemic against Lutheran Kabbalist Jakob Böhme and early continental Theosophy, which itself was influenced by Kabbalah. It also includes a summary describing much of how Luranic Kabbalah was adopted in Protestant circles in the late 17th century, and features the oldest known diagram of the sefirot (tree of life) in North America.

Another key figure is Harvard’s first Hebrew instructor, Judah Monis, who referred to himself as the “last Jew and first congregationalist in the line of an authentic transmission of Kabbalah into the colleges of America.”31 Monis's baptismal discourses were filled with Kabbalistic language and doctrines to accommodate Jewish converts. He became a major influence on later Congregationalist ministers like Yale’s president Ezra Stiles.

Both Monis and Stiles focused intensely on the Shema as a theurgic recital of unification combining its three-fold repetition of divine names with Kabbalistic numerology (Gematria) to affirm the Trinity, an idea that derives from the Christian Kabbalists of the Renaissance. Gematria is the alchemical rearranging of letters and words to ascribe new meaning (temura) in the same way that Kabbalists aim to magically reshape reality. This method is used to “decode” Christian mysteries throughout Monis’s document titled “Nothing But the Truth,” which ironically contains nothing but judaizing heresy.

Regarding this schizophrenic approach to biblical interpretation, Heiromonk Job Gumerov reminds us:

This occult numerical and alphabetic magic has nothing to do with the meaning of Scripture. Biblical texts do not continue any code or cipher. Parables, images and symbols – are just means that return the deep theological truths of our salvation, different to express in human language.32

While Kabbalistic tradition understood these symbols as pointing to the ten sefirot, or emanations, the esoteric Puritans synthesized them with Christian theology. Monis and the Christian Kabbalists before him understood Adam Kadmon to embody an “outer and inner Christ”, using the Nishmat Christi theurgic prayer to unify the so-called “messianic spark” within all mankind.

At Yale, President Ezra Stiles regularly attended synagogue services in Newport and studied Kabbalistic texts with visiting rabbis. Stiles envisioned Yale as parallel to the great yeshivas of old and sought to incorporate Jewish learning into American college education, once stating that he felt Kabbalistic learning was “worthy to be transplanted into the colleges of America.”33

Stiles even corresponded with Benjamin Franklin in London to request copies of the Zohar. Thomas Jefferson further reveals the continued influence of Christian Kabbalism among the founding fathers, as he wrote in his 1813 letter to John Adams:

To compare the morals of the old, with those of the New Testament, would require an attentive study of the former, a search through all its books for its precepts, and through all its history for its practices, and the principles they prove. As commentaries too on these, the philosophy of the Hebrews must be enquired into, their Mishna, their Gemara, Cabbala, Jezirah, Zohar, Cosri and their Talmud must be examined and understood, in order to do them full justice.34

The founding fathers also incorporated the Kabbalistic concept of Shekinah, the “feminine half of God”, in their initial Great Seal design proposed by Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams, immediately after signing the Declaration of Independence. The seal featured Moses parting the Red Sea, with “Rays from a Pillar of Fire in the Cloud, expressive of the divine Presence and Command.”35 Ogren argues this placement of the Shekinah was intentional and evidenced by the influence of Jewish mystical thought of both Franklin and Jefferson. Although it was rejected by Congress, the original seal depicts the notion held by the early American Pilgrims that it was the Shekinah that guided them through the Atlantic.

Six years later, Congress would go on to approve Charles Thomson’s Great Seal which also contains a Shekinah cloud above the bald eagle, featuring even more mystical Jewish symbolism than Franklin’s. Inside the Shekinah, there are thirteen stars creating a hexagram, a Kabbalistic symbol representing the “primal transsexual” Adam Kadmon, who embodies “the union of male and female forces (Shekinah).”36 As legend has it, the inclusion of this occult symbol was George Washington’s debt owed to Haym Salomon for financing the Revolutionary War, who wanted nothing more than to pay tribute to the Jewish people.37

These esoteric symbols we carry with us on our currency to this day should serve as a reminder that the American ethos was not established upon anything that resembles apostolic Christianity, but a form of Christian Humanism synthesized with revolutionary Kabbalistic doctrines.

The Shekinah Question

The presence of Shekinah as a doctrine in modern evangelical theology sheds light on how fragments of Kabbalistic influence remain in Protestant thought to this day. But to understand the Protestant adaptation of this doctrine at the core of Kabbalah, we must first uncover both its esoteric meaning and its symbolic role in the creation of the new world.

In the Zohar, Shekinah is the feminine indwelling of the Jewish god and represents the final emanation of Ein Sof (the "nameless being") into the material world. Kabbalists associate shekinah with a divine feminine manifestation of God which appeared as clouds of glory guiding the Israelites through exile in a “protective maternal presence on the Israelites’ journey from slavery to freedom.”38 According to Scholem, “The introduction of this idea was one of the most important and lasting innovations of Kabbalism...no other element of Kabbalism won such a degree of popular approval.”39

Kabbalists relate the forced separation of Shekinah from the Ein Sof to the Jews' exile from their homeland. Restoring Shekinah involves redeeming scattered “sparks of holiness" from the shattered vessels of creation to achieve “world repair” (tikkun). It doesn’t take much stretch of the imagination to realize how often this archetype appears in our modern literature, film, and myths. And in case this doctrine already seems stranger than fiction, it’s about to take a satanic turn.

To gather the divine sparks and restore Sehkinah, a sexual union occurs within Ein Sof via the Yesof emanation (Ein Sof’s literal phallus), which is the goal of the sefirot. This can be seen in the practice of davening, a theurgic pelvic-thrusting ritual that Hassidim perform to copulate with their Kabbalistic goddess. Rabbi Jacob Schochet explicitly describes davening as being “based on the analogy of the movement that occurs in the act of love making.”40

While the perverse davening ritual is an important method of restoring the Shekinah, Scholem explains another dark role human actions play as a vehicle of world repair:

“But the essential function of the Law, both of the Noahide law binding on all men and of the Torah imposed specially upon Israel, is to serve as an instrument of the tikkun. Every man who acts in accordance with this Law brings home the fallen sparks of the Shekinah and of his own soul as well. He restores the pristine perfection of his own spiritual body…

In redemption everything is restored to its place by the secret magic of human acts…every commandment has its mystical aspect whose observance creates a bond between the world of man and the world of the Sefirot…

Thus fundamentally every man and especially every Jew participates in the process of the tikkun.”41

Obedience to the Noahide laws which Scholem mentions here is a requirement to usher in the Jewish messianic age. The seven Noahide laws derive from Sanhedrin 56a of the Babylonian Talmud, where they are systematically numbered and described as universally binding on all humanity. According to the Talmud, non-Jews are not obligated to convert to Judaism, but they are required to observe the Seven Laws of Noah to be assured of a place in the “World to Come.”

Rabbi Michael Higger explains how Noahide laws will apply to Gentiles during the Jewish messianic period in which “a number of ordinances will, therefore…be offered to the non-Jewish peoples—especially precepts, the observances of which symbolizes universal truths concerning God and the ideal Israel.”42

The first Noahide law contains an explicit prohibition of idolatry punishable by death, which incriminates Christians for their worship of Christ. In the seventh law is a notable injunction to enforce the other six laws by establishing courts of justice. Although the Noahide laws are not universally in effect, they’ve already made their way into U.S. Public Law, thanks to the growing political and evangelical support of Zionist rule:

“On March 26, 1991 the U.S. Congress, under the presidency of George H.W. Bush, established the Seven Noachide Laws as Public Law 102-14 in honor of Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch.”43

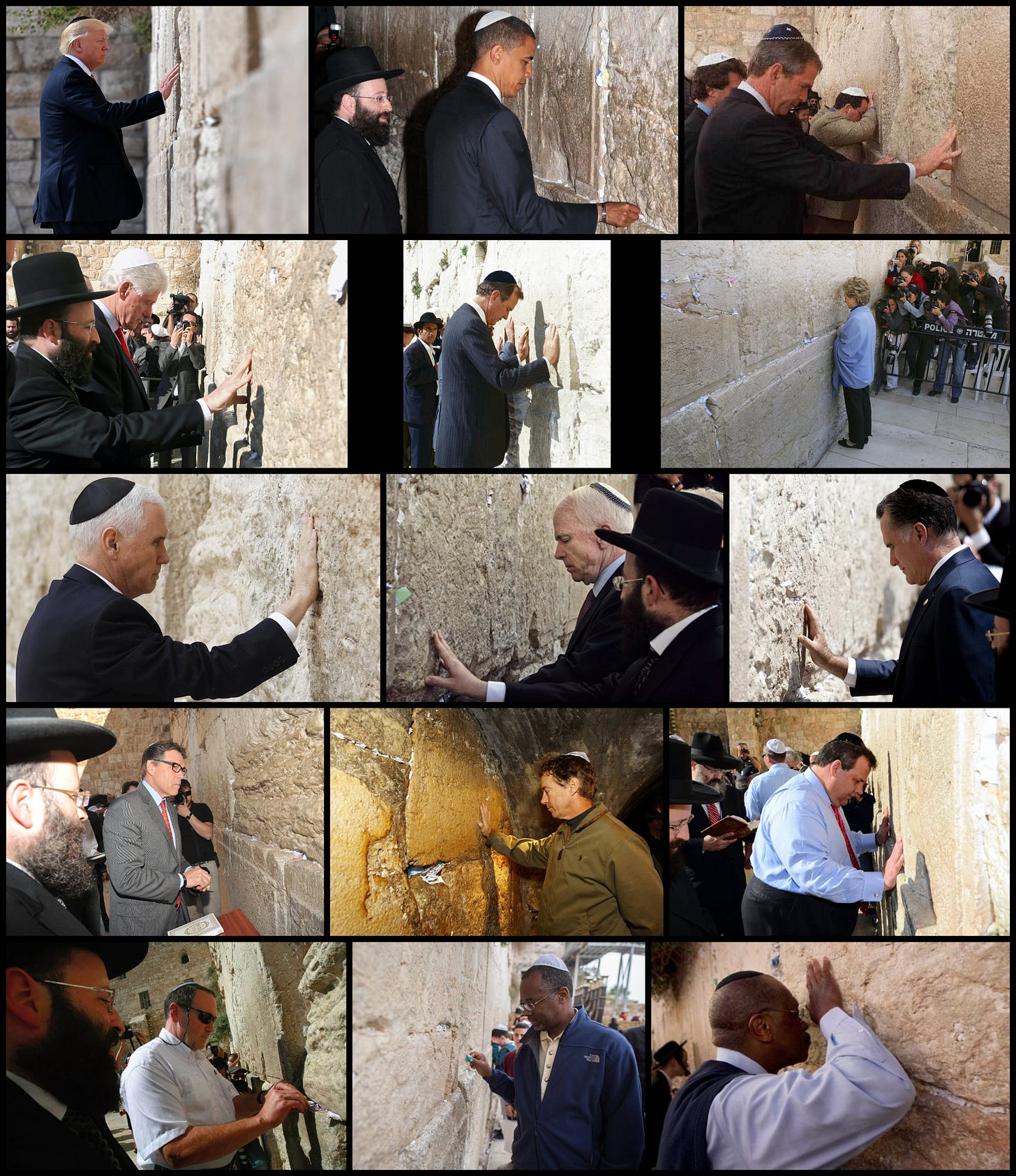

It is no wonder why countless world leaders and evangelicals are increasingly subjected to a tamer version of the theurgic ritual to repair the world at the so-called Western Wall. Kabbalists believe this is where the Shekinah’s presence is particularly strong, closest to where it once dwelled in the former Holy of Holies. Any form of Christian participation in this ritual is not a mere paying of respects to “God’s chosen people”, it is symbolic of the hastening of Christian persecutions in the age of antichrist.

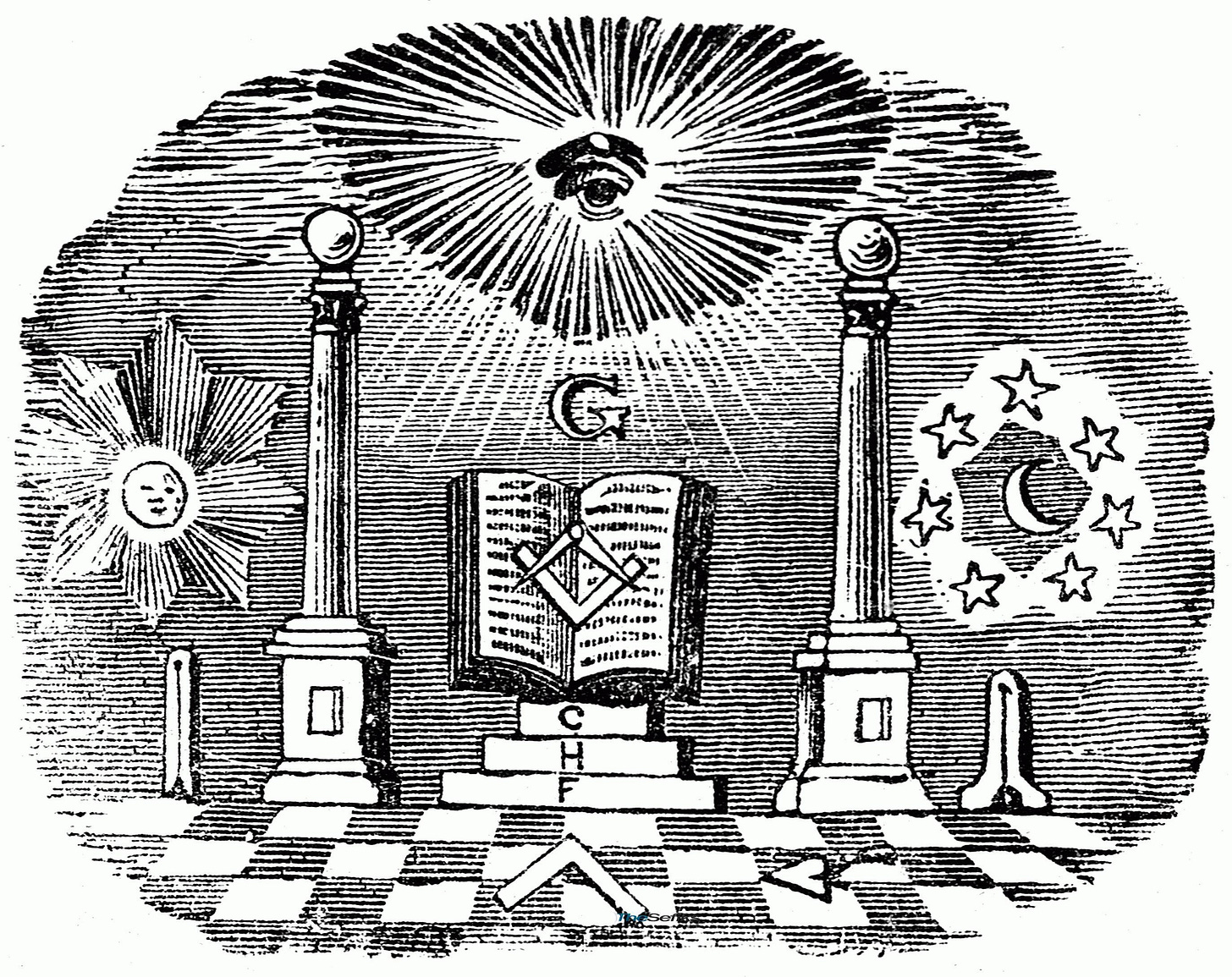

Throughout the years, many Protestant theologians have adapted a revised usage of Shekinah, attributing it to the divine manifestation of the glory of God. In Truths We Confess, R.C. Sproul states: "Christ was carried up into heaven on the shekinah cloud." The renowned Calvinist theologian B.B. Warfield in his book The Lord of Glory, ascribes the word Shekinah to Christ; perhaps derived from the Masonic lodge he belonged to, where the Shekinah is prominently depicted between the twin pillars.

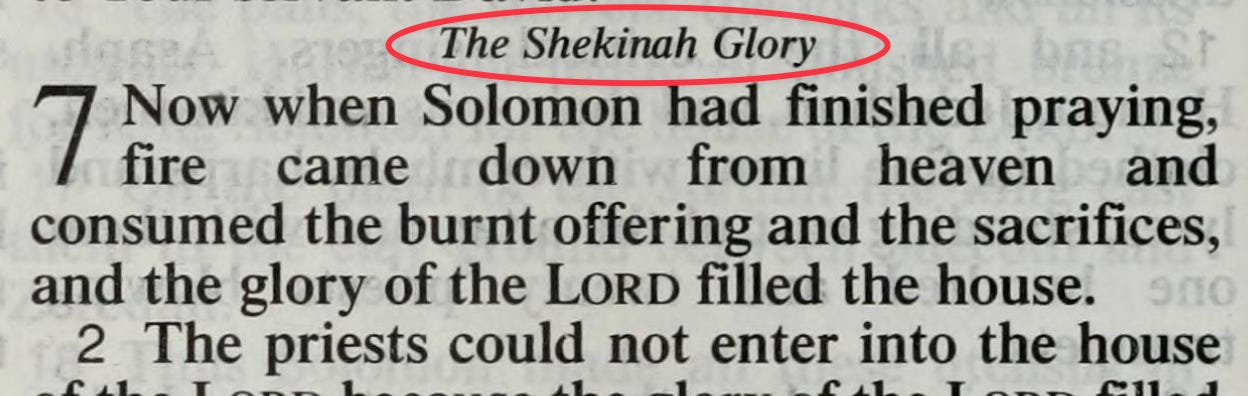

Many other leading evangelical pastors, such as John Piper and John MacArthur, teach Shekinah is biblical while appealing to Sola Scriptura, despite the word being completely absent from the bible. Shekinah was even added as a section title for 2 Chronicles chapter 7 in the New American Standard Bible translation, and appears seventeen times in the MacArthur Study Bible.

One might argue that regardless of the Hebrew word not appearing in the Bible, the doctrine of Shekinah as a manifestation of God’s glory is biblically sound; yet the mere usage of this exclusively rabbinical term begs the question: How did it end up in Protestant theology?

This goes to show that throughout the centuries, Protestant theologians have maintained their own type of oral and written transmission of rabbinical thought, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

Afterword: Dear reader, thank you for your support in the publishing of this article. Without your contributions, the countless hours researching and compiling this knowledge in written form would not have been possible. Please pray for me, the servant of God Anthony, as continuing this work comes with many spiritual challenges.

In the next part, we will explore the development of Christian Zionism through the Protestant revolution and its spiritual and earthly consequences.

“Kabbalah’s Dissemination around the World Is the Messiah’s Horn — Laitman.com.” 2025. Laitman.com. 2025. https://laitman.com/2009/09/kabbalahs-dissemination-around-the-world-is-the-messiahs-horn/.

Scholem, Gershom. 1965. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. Schocken Books Inc: New York, NY. 113.

Ibid., 23.

St. Ignatius of Antioch to the Magnesians (Roberts-Donaldson translation). Earlychristianwritings.com. 2006-02-02.

Newman, 373. (The Bavarian Jews were charged with secretly funding and arming the Hussite military revolution.)

Ibid.

Jones, E. Michael. 2020. The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History. Second edition. Vol. 1. 3 vols. South Bend, Ind.: Fidelity Press. p.296 (cited in Walsh, Philip II, p.259)

Johnson, Matthew Raphael. 2018. “The Orthodox Nationalist: Jews, Kabbalah and the Protestant Reformation. TON 102418.” Radioalbion.com. October 24, 2018. https://www.radioalbion.com/2018/10/the-orthodox-nationalist-jews-kabbalah.html.

Jones, 281.

According to Gershom Scholem's research presented in his work “Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism”, the Zohar was proven to not be an ancient text as Hermetic Kabbalists believed, but rather a medieval composition that developed in stages over about 60 years. Similarly, Isaac Casaubon discovered the Corpus Hermeticum was falsely dated back to the time of Moses and was actually a 4th century work.

Owens, Lance. 2024. “Joseph Smith and Kabbalah: The Occult Connection.” ResearchGate, October. https://doi.org/10.2307/45225963.

Jones, 296. (cited in Walsh, Philip II, 248.)

Newman, 407.

Lutheri, Martini D. 1844. Commentarium in Epistolam S. Pauli ad Galatas: 2. Erlangae

Hazlitt, William, trans. 1872. The Table Talk of Martin Luther. London. 326.

Johnson, 2018

Ogren, Brian. 2021. Kabbalah and the Founding of America: The Early Influence of Jewish Thought in the New World. New York (N.Y.): NYU Press. 120.

Rose, Fr Seraphim. 1975. The Orthodox Survival Course. 2nd Edition (Draft Copy). Samizdat Press. 17.

Jones, p.281

Graetz, Heinrich. 1894. The History of the Jews. Vol. II. The Jewish Publication Society of America. Philadelphia. 67. Cited in Jones, 282.

Magee, Glenn. 2010. Hegel’s Philosophy of History and Kabbalist Eschatology. Dudley, Will (editor). Hegel and History. State University of New York Press. 238.

TheCustodian. 2016. “The Enchanted House of Justinus Kerner - the Thinker’s Garden.” The Thinker’s Garden. December 12, 2016. https://thethinkersgarden.com/odd-truths-the-enchanted-house-of-justinus-kerner/.

Ibid., 243.

Newman, 413.

“History of the Christian Church, Schaff, 1910. Vol. VIII, ch. 3, § 19. “The Abolition of the Roman Worship. 1524.” Bible.ca. 2025. https://www.bible.ca/history/philip-schaff/8_ch03.htm.

Harkness, Georgia. John Calvin: The Man and His Ethics. Abingdon Press. New York. p. 94; summarizing Calvin’s Sermon on Galatians 1:8-9, from Opera, I, 326.

"Shulchan-Aruch – Chapter 11". Torah.org. Archived from the original on 2000-04-21. Retrieved 2012-09-19.

Rose, 22.

Ogren, 53.

Quinn, D Michael. 1998. Early Mormonism and the Magic Worldview. Signature Books: Salt Lake City.

Ogren, 136.,

Hieromonk Job (Gumerov). What is Kabbalah? / Orthodoxy.Ru. 2016. https://pravoslavie.ru/6905.html](https://pravoslavie.ru/6905.html

Ibid., 142.

“Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 12 October 1813.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-06-02-0431.

“Benjamin Franklin’s Great Seal Design.” 2025. Greatseal.com. 2025. https://www.greatseal.com/committees/firstcomm/reverse.html.

Hoffman, Michael. 2011. Judaism’s Strange Gods. Coeur d’Alene, Idaho: Independent History and Research. 291.

Chabad.org. 2021. “Haym Salomon: The Man Who Financed the American Revolution - a Jewish American Hero.” @Chabad. July 3, 2021. https://www.chabad.org/library/article\_cdo/aid/5175340/jewish/Haym-Salomon-The-Man-Who-Financed-the-American-Revolution.htm.

Learning, My Jewish. 2003. “Shekhinah: The Divine Feminine.” My Jewish Learning. April 21, 2003. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-divine-feminine-in-kabbalah-an-example-of-jewish-renewal/.

Scholem, Gershom G. 1941. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. 3d rev'd ed: reprint 1961. Jerusalem: Schocken. 229

Schochet, Jacob I. 1998. Tzavat HaRivash. Kehot Publication: Brooklyn, NY, pp.54-55.

Scholem, Gershom. 1965. On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism. Shocken Books Inc. New York, NY. p. 116., Scholem, Gershom. 1974. Kabbalah. Dorset Press, Keter Publishing House Jerusalem Ltd: New York, NY. 176.

Higger, Michael. 1932. The Jewish Utopia. CPA Books Inc. 106.

Chabad.org. 2002. “The 7 Noahide Laws.” @Chabad. October 31, 2002. https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/62221/jewish/The-7-Noahide-Laws.htm.

This was a great read. Looking forward to pt 2

Excellent research Anthony!